When a Helm chart fails in production, the impact is immediate and visible. A misconfigured ServiceAccount, a typo in a ConfigMap key, or an untested conditional in templates can trigger incidents that cascade through your entire deployment pipeline. The irony is that most teams invest heavily in testing application code while treating Helm charts as “just configuration.”

Helm charts are infrastructure code. They define how your applications run, scale, and integrate with the cluster. Treating them with less rigor than your application logic is a risk most production environments cannot afford.

The Real Cost of Untested Charts

In late 2024, a medium-sized SaaS company experienced a 4-hour outage because a chart update introduced a breaking change in RBAC permissions. The chart had been tested locally with helm install --dry-run, but the dry-run validation doesn’t interact with the API server’s RBAC layer. The deployment succeeded syntactically but failed operationally.

The incident revealed three gaps in their workflow:

- No schema validation against the target Kubernetes version

- No integration tests in a live cluster

- No policy enforcement for security baselines

These gaps are common. According to a 2024 CNCF survey on GitOps practices, fewer than 40% of organizations systematically test Helm charts before production deployment.

The problem is not a lack of tools—it’s understanding which layer each tool addresses.

Testing Layers: What Each Level Validates

Helm chart testing is not a single operation. It requires validation at multiple layers, each catching different classes of errors.

Layer 1: Syntax and Structure Validation

What it catches: Malformed YAML, invalid chart structure, missing required fields

Tools:

helm lint: Built-in, minimal validation following Helm best practicesyamllint: Strict YAML formatting rules

Example failure caught:

# Invalid indentation breaks the chart

resources:

limits:

cpu: "500m"

memory: "512Mi" # Incorrect indentation

Limitation: Does not validate whether the rendered manifests are valid Kubernetes objects.

Layer 2: Schema Validation

What it catches: Manifests that would be rejected by the Kubernetes API

Primary tool: kubeconform

Kubeconform is the actively maintained successor to the deprecated kubeval. It validates against OpenAPI schemas for specific Kubernetes versions and can include custom CRDs.

Project Profile:

- Maintenance: Active, community-driven

- Strengths: CRD support, multi-version validation, fast execution

- Why it matters:

helm lintvalidates chart structure, but not if rendered manifests match Kubernetes schemas

Example failure caught:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

spec:

replicas: 2

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: myapp

spec:

containers:

- name: app

image: nginx:latest

# Missing required field: spec.selector

Configuration example:

helm template my-chart . | kubeconform \

-kubernetes-version 1.30.0 \

-schema-location default \

-schema-location 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/datreeio/CRDs-catalog/main/{{.Group}}/{{.ResourceKind}}_{{.ResourceAPIVersion}}.json' \

-summary

Example CI integration:

#!/bin/bash

set -e

KUBE_VERSION="1.30.0"

echo "Rendering chart..."

helm template my-release ./charts/my-chart > manifests.yaml

echo "Validating against Kubernetes $KUBE_VERSION..."

kubeconform \

-kubernetes-version "$KUBE_VERSION" \

-schema-location default \

-summary \

-output json \

manifests.yaml | jq -e '.summary.invalid == 0'

Alternative: kubectl --dry-run=server (requires cluster access, validates against actual API server)

Layer 3: Unit Testing

What it catches: Logic errors in templates, incorrect conditionals, wrong value interpolation

Unit tests validate that given a set of input values, the chart produces the expected manifests. This is where template logic is verified before reaching a cluster.

Primary tool: helm-unittest

helm-unittest is the most widely adopted unit testing framework for Helm charts.

Project Profile:

- GitHub: 3.3k+ stars, ~100 contributors

- Maintenance: Active (releases every 2-3 months)

- Primary maintainer: Quentin Machu (originally @QubitProducts, now independent)

- Commercial backing: None

- Bus Factor: Medium-High (no institutional backing, but consistent community engagement)

Strengths:

- Fast execution (no cluster required)

- Familiar test syntax (similar to Jest/Mocha)

- Snapshot testing support

- Good documentation

Limitations:

- Doesn’t validate runtime behavior

- Cannot test interactions with admission controllers

- No validation against actual Kubernetes API

Example test scenario:

# tests/deployment_test.yaml

suite: test deployment

templates:

- deployment.yaml

tests:

- it: should set resource limits when provided

set:

resources.limits.cpu: "1000m"

resources.limits.memory: "1Gi"

asserts:

- equal:

path: spec.template.spec.containers[0].resources.limits.cpu

value: "1000m"

- equal:

path: spec.template.spec.containers[0].resources.limits.memory

value: "1Gi"

- it: should not create HPA when autoscaling disabled

set:

autoscaling.enabled: false

template: hpa.yaml

asserts:

- hasDocuments:

count: 0

Alternative: Terratest (Helm module)

Terratest is a Go-based testing framework from Gruntwork that includes first-class Helm support. Unlike helm-unittest, Terratest deploys charts to real clusters and allows programmatic assertions in Go.

Example Terratest test:

func TestHelmChartDeployment(t *testing.T) {

kubectlOptions := k8s.NewKubectlOptions("", "", "default")

options := &helm.Options{

KubectlOptions: kubectlOptions,

SetValues: map[string]string{

"replicaCount": "3",

},

}

defer helm.Delete(t, options, "my-release", true)

helm.Install(t, options, "../charts/my-chart", "my-release")

k8s.WaitUntilNumPodsCreated(t, kubectlOptions, metav1.ListOptions{

LabelSelector: "app=my-app",

}, 3, 30, 10*time.Second)

}

When to use Terratest vs helm-unittest:

- Use

helm-unittestfor fast, template-focused validation in CI - Use

Terratestwhen you need full integration testing with Go flexibility

Layer 4: Integration Testing

What it catches: Runtime failures, resource conflicts, actual Kubernetes behavior

Integration tests deploy the chart to a real (or ephemeral) cluster and verify it works end-to-end.

Primary tool: chart-testing (ct)

chart-testing is the official Helm project for testing charts in live clusters.

Project Profile:

- Ownership: Official Helm project (CNCF)

- Maintainers: Helm team (contributors from Microsoft, IBM, Google)

- Governance: CNCF-backed with public roadmap

- LTS: Aligned with Helm release cycle

- Bus Factor: Low (institutional backing from CNCF provides strong long-term guarantees)

Strengths:

- De facto standard for public Helm charts

- Built-in upgrade testing (validates migrations)

- Detects which charts changed in a PR (efficient for monorepos)

- Integration with GitHub Actions via official action

Limitations:

- Requires a live Kubernetes cluster

- Initial setup more complex than unit testing

- Does not include security scanning

What ct validates:

- Chart installs successfully

- Upgrades work without breaking state

- Linting passes

- Version constraints are respected

Example ct configuration:

# ct.yaml

target-branch: main

chart-dirs:

- charts

chart-repos:

- bitnami=https://charts.bitnami.com/bitnami

helm-extra-args: --timeout 600s

check-version-increment: true

Typical GitHub Actions workflow:

name: Lint and Test Charts

on: pull_request

jobs:

lint-test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v3

with:

fetch-depth: 0

- name: Set up Helm

uses: azure/setup-helm@v3

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v4

with:

python-version: '3.11'

- name: Set up chart-testing

uses: helm/chart-testing-action@v2

- name: Run chart-testing (lint)

run: ct lint --config ct.yaml

- name: Create kind cluster

uses: helm/kind-action@v1

- name: Run chart-testing (install)

run: ct install --config ct.yaml

When ct is essential:

- Public chart repositories (expected by community)

- Charts with complex upgrade paths

- Multi-chart repositories with CI optimization needs

Layer 5: Security and Policy Validation

What it catches: Security misconfigurations, policy violations, compliance issues

This layer prevents deploying charts that pass functional tests but violate organizational security baselines or contain vulnerabilities.

Policy Enforcement: Conftest (Open Policy Agent)

Conftest is the CLI interface to Open Policy Agent for policy-as-code validation.

Project Profile:

- Parent: Open Policy Agent (CNCF Graduated Project)

- Governance: Strong CNCF backing, multi-vendor support

- Production adoption: Netflix, Pinterest, Goldman Sachs

- Bus Factor: Low (graduated CNCF project with multi-vendor backing)

Strengths:

- Policies written in Rego (reusable, composable)

- Works with any YAML/JSON input (not Helm-specific)

- Can enforce organizational standards programmatically

- Integration with admission controllers (Gatekeeper)

Limitations:

- Rego has a learning curve

- Does not replace functional testing

Example Conftest policy:

# policy/security.rego

package main

import future.keywords.contains

import future.keywords.if

import future.keywords.in

deny[msg] {

input.kind == "Deployment"

container := input.spec.template.spec.containers[_]

not container.resources.limits.memory

msg := sprintf("Container '%s' must define memory limits", [container.name])

}

deny[msg] {

input.kind == "Deployment"

container := input.spec.template.spec.containers[_]

not container.resources.limits.cpu

msg := sprintf("Container '%s' must define CPU limits", [container.name])

}

Running the validation:

helm template my-chart . | conftest test -p policy/ -

Alternative: Kyverno

Kyverno offers policy enforcement using native Kubernetes manifests instead of Rego. Policies are written in YAML and can validate, mutate, or generate resources.

Example Kyverno policy:

apiVersion: kyverno.io/v1

kind: ClusterPolicy

metadata:

name: require-resource-limits

spec:

validationFailureAction: Enforce

rules:

- name: check-container-limits

match:

resources:

kinds:

- Pod

validate:

message: "All containers must have CPU and memory limits"

pattern:

spec:

containers:

- resources:

limits:

memory: "?*"

cpu: "?*"

Conftest vs Kyverno:

- Conftest: Policies run in CI, flexible for any YAML

- Kyverno: Runtime enforcement in-cluster, Kubernetes-native

Both can coexist: Conftest in CI for early feedback, Kyverno in cluster for runtime enforcement.

Vulnerability Scanning: Trivy

Trivy by Aqua Security provides comprehensive security scanning for Helm charts.

Project Profile:

- Maintainer: Aqua Security (commercial backing with open-source core)

- Scope: Vulnerability scanning + misconfiguration detection

- Helm integration: Official

trivy helmcommand - Bus Factor: Low (commercial backing + strong open-source adoption)

What Trivy scans in Helm charts:

- Vulnerabilities in referenced container images

- Misconfigurations (similar to Conftest but pre-built rules)

- Secrets accidentally committed in templates

Example scan:

trivy helm ./charts/my-chart --severity HIGH,CRITICAL --exit-code 1

Sample output:

myapp/templates/deployment.yaml (helm)

====================================

Tests: 12 (SUCCESSES: 10, FAILURES: 2)

Failures: 2 (HIGH: 1, CRITICAL: 1)

HIGH: Container 'app' of Deployment 'myapp' should set 'securityContext.runAsNonRoot' to true

════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Ensure containers run as non-root users

See https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/security/pod-security-standards/

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

myapp/templates/deployment.yaml:42

Commercial support:

Aqua Security offers Trivy Enterprise with advanced features (centralized scanning, compliance reporting). For most teams, the open-source version is sufficient.

Other Security Tools

Polaris (Fairwinds)

Polaris scores charts based on security and reliability best practices. Unlike enforcement tools, it provides a health score and actionable recommendations.

Use case: Dashboard for chart quality across a platform

Checkov (Bridgecrew/Palo Alto)

Similar to Trivy but with a broader IaC focus (Terraform, CloudFormation, Kubernetes, Helm). Pre-built policies for compliance frameworks (CIS, PCI-DSS).

When to use Checkov:

- Multi-IaC environment (not just Helm)

- Compliance-driven validation requirements

Enterprise Selection Criteria

Bus Factor and Long-Term Viability

For production infrastructure, tool sustainability matters as much as features. Community support channels like Helm CNCF Slack (#helm-users, #helm-dev) and CNCF TAG Security provide valuable insights into which projects have active maintainer communities.

Questions to ask:

- Is the project backed by a foundation (CNCF, Linux Foundation)?

- Are multiple companies contributing?

- Is the project used in production by recognizable organizations?

- Is there a public roadmap?

Risk Classification:

| Tool | Governance | Bus Factor | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| chart-testing | CNCF | Low | Helm official project |

| Conftest/OPA | CNCF Graduated | Low | Multi-vendor backing |

| Trivy | Aqua Security | Low | Commercial backing + OSS |

| kubeconform | Community | Medium | Active, but single maintainer |

| helm-unittest | Community | Medium-High | No institutional backing |

| Polaris | Fairwinds | Medium | Company-sponsored OSS |

Kubernetes Version Compatibility

Tools must explicitly support the Kubernetes versions you run in production.

Red flags:

- No documented compatibility matrix

- Hard-coded dependencies on old K8s versions

- No testing against multiple K8s versions in CI

Example compatibility check:

# Does the tool support your K8s version?

kubeconform --help | grep -A5 "kubernetes-version"

For tools like ct, always verify they test against a matrix of Kubernetes versions in their own CI.

Commercial Support Options

When commercial support matters:

- Regulatory compliance requirements (SOC2, HIPAA, etc.)

- Limited internal expertise

- SLA-driven operations

Available options:

- Trivy: Aqua Security offers Trivy Enterprise

- OPA/Conftest: Styra provides OPA Enterprise

- Terratest: Gruntwork offers consulting and premium modules

Most teams don’t need commercial support for chart testing specifically, but it’s valuable in regulated industries where audits require vendor SLAs.

Security Scanner Integration

For enterprise pipelines, chart testing tools should integrate cleanly with:

- SIEM/SOAR platforms

- CI/CD notification systems

- Security dashboards (e.g., Grafana, Datadog)

Required features:

- Structured output formats (JSON, SARIF)

- Exit codes for CI failure

- Support for custom policies

- Webhook or API for event streaming

Example: Integrating Trivy with SIEM

# .github/workflows/security.yaml

- name: Run Trivy scan

run: trivy helm ./charts --format json --output trivy-results.json

- name: Send to SIEM

run: |

curl -X POST https://siem.company.com/api/events \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d @trivy-results.json

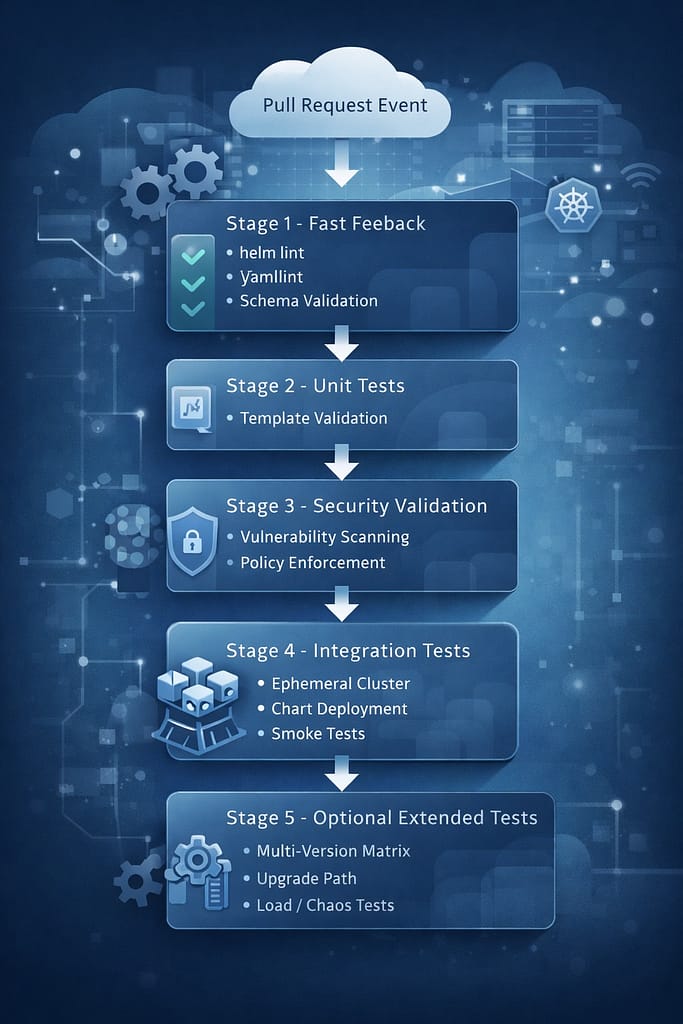

Testing Pipeline Architecture

A production-grade Helm chart pipeline combines multiple layers:

Pipeline efficiency principles:

- Fail fast: syntax and schema errors should never reach integration tests

- Parallel execution where possible (unit tests + security scans)

- Cache ephemeral cluster images to reduce setup time

- Skip unchanged charts (ct built-in change detection)

Decision Matrix: When to Use What

Scenario 1: Small Team / Early-Stage Startup

Requirements: Minimal overhead, fast iteration, reasonable safety

Recommended Stack:

Linting: helm lint + yamllint

Validation: kubeconform

Security: trivy helm

Optional: helm-unittest (if template logic becomes complex)

Rationale: Zero-dependency baseline that catches 80% of issues without operational complexity.

Scenario 2: Enterprise with Compliance Requirements

Requirements: Auditable, comprehensive validation, commercial support available

Recommended Stack:

Linting: helm lint + yamllint

Validation: kubeconform

Unit Tests: helm-unittest

Security: Trivy Enterprise + Conftest (custom policies)

Integration: chart-testing (ct)

Runtime: Kyverno (admission control)

Optional: Terratest for complex upgrade scenarios

Rationale: Multi-layer defense with both pre-deployment and runtime enforcement. Commercial support available for security components.

Scenario 3: Multi-Tenant Internal Platform

Requirements: Prevent bad charts from affecting other tenants, enforce standards at scale

Recommended Stack:

CI Pipeline:

• helm lint → kubeconform → helm-unittest → ct

• Conftest (enforce resource quotas, namespaces, network policies)

• Trivy (block critical vulnerabilities)

Runtime:

• Kyverno or Gatekeeper (enforce policies at admission)

• ResourceQuotas per namespace

• NetworkPolicies by default

Additional tooling:

- Polaris dashboard for chart quality scoring

- Custom admission webhooks for platform-specific rules

Rationale: Multi-tenant environments cannot tolerate “soft” validation. Runtime enforcement is mandatory.

Scenario 4: Open Source Public Charts

Requirements: Community trust, transparent testing, broad compatibility

Recommended Stack:

Must-have:

• chart-testing (expected standard)

• Public CI (GitHub Actions with full logs)

• Test against multiple K8s versions

Nice-to-have:

• helm-unittest with high coverage

• Automated changelog generation

• Example values for common scenarios

Rationale: Public charts are judged by testing transparency. Missing ct is a red flag for potential users.

The Minimum Viable Testing Stack

For any environment deploying Helm charts to production, this is the baseline:

Layer 1: Pre-Commit (Developer Laptop)

helm lint charts/my-chart

yamllint charts/my-chart

Layer 2: CI Pipeline (Automated on PR)

# Fast validation

helm template my-chart ./charts/my-chart | kubeconform \

-kubernetes-version 1.30.0 \

-summary

# Security baseline

trivy helm ./charts/my-chart --exit-code 1 --severity CRITICAL,HIGH

Layer 3: Pre-Production (Staging Environment)

# Integration test with real cluster

ct install --config ct.yaml --charts charts/my-chart

Time investment:

- Initial setup: 4-8 hours

- Per-PR overhead: 3-5 minutes

- Maintenance: ~1 hour/month

ROI calculation:

Average production incident caused by untested chart:

- Detection: 15 minutes

- Triage: 30 minutes

- Rollback: 20 minutes

- Post-mortem: 1 hour

- Total: ~2.5 hours of engineering time

If chart testing prevents even one incident per quarter, it pays for itself in the first month.

Common Anti-Patterns to Avoid

Anti-Pattern 1: Only using --dry-run

helm install --dry-run validates syntax but skips:

- Admission controller logic

- RBAC validation

- Actual resource creation

Better: Combine dry-run with kubeconform and at least one integration test.

Anti-Pattern 2: Testing only in production-like clusters

“We test in staging, which is identical to production.”

Problem: Staging clusters rarely match production exactly (node counts, storage classes, network policies). Integration tests should run in isolated, ephemeral environments.

Anti-Pattern 3: Security scanning without enforcement

Running trivy helm without failing the build on critical findings is theater.

Better: Set --exit-code 1 and enforce in CI.

Anti-Pattern 4: Ignoring upgrade paths

Most chart failures happen during upgrades, not initial installs. Chart-testing addresses this with ct install --upgrade.

Conclusion: Testing is Infrastructure Maturity

The gap between teams that test Helm charts and those that don’t is not about tooling availability—it’s about treating infrastructure code with the same discipline as application code.

The cost of testing is measured in minutes per PR. The cost of not testing is measured in hours of production incidents, eroded trust in automation, and teams reverting to manual deployments because “Helm is too risky.”

The testing stack you choose matters less than the fact that you have one. Start with the minimal viable stack (lint + schema + security), run it consistently, and expand as your charts become more complex.

By implementing a structured testing pipeline, you catch 95% of chart issues before they reach production. The remaining 5% are edge cases that require production observability, not more testing layers.

Helm chart testing is not about achieving perfection—it’s about eliminating the preventable failures that undermine confidence in your deployment pipeline.