Discover how to extract all the information available to inject it into your pods

Photo by James Harrison on Unsplash

Kubernetes Metadata is how you will access some of the information from your pods in your application at runtime. When you are moving from a traditional kind of development to a cloud-native one, you usually need to access some out-of-the-box information available in a conventional environment.

This happens especially when we are talking about a platform that in the past was deployed on any platform that was populated with some information such as application name, version, domain, and so on. But this is tricky in a cloud-native approach. Or maybe not, But at least for some time, you have been wondering how you can get access to some of the information you know about your cloud-native workload, so the running application inside the pod knows it as well.

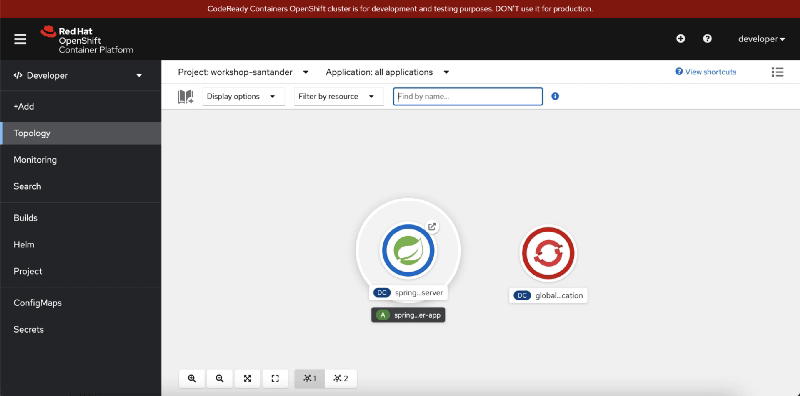

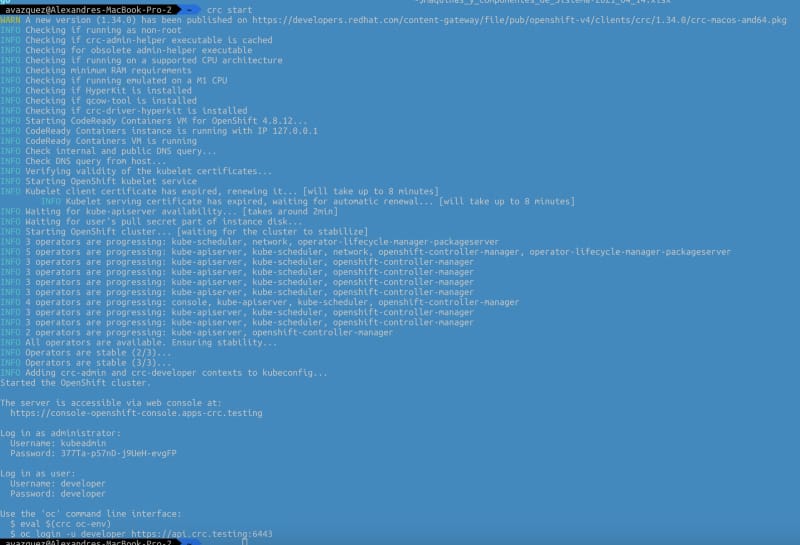

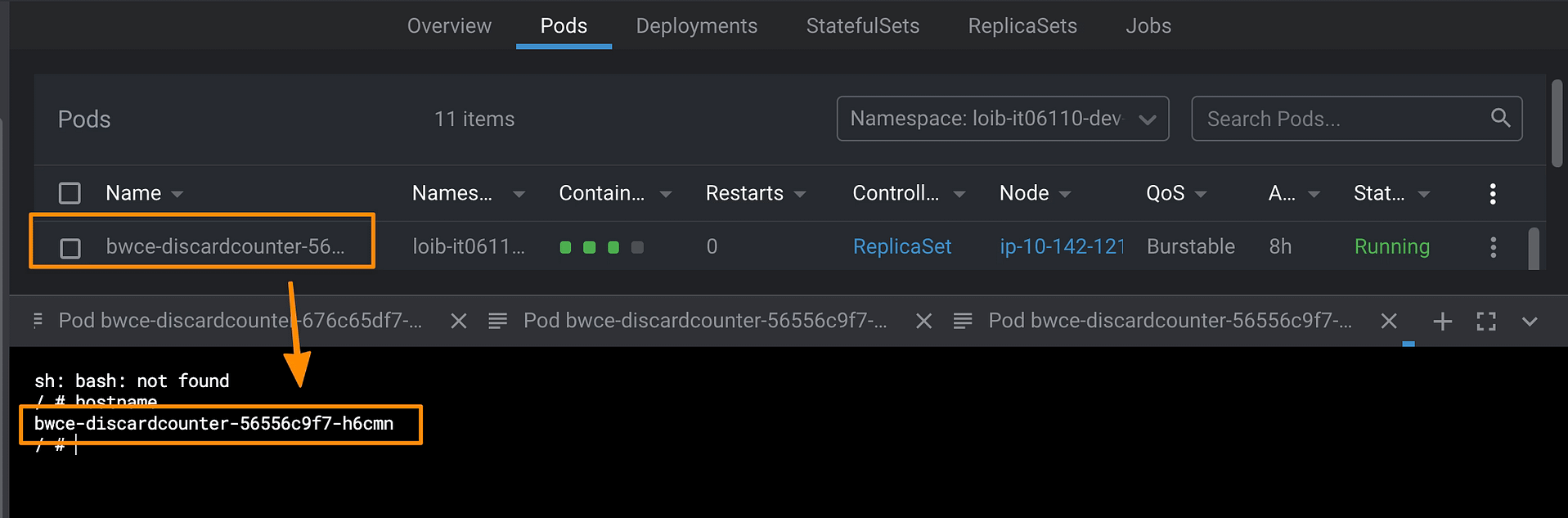

Because when you define a cloud-native, you describe a lot of very relevant information. For example, let’s think about that. When you start your pod, you know your pod name because it is your hostname:

But when you define your workload, you have a deployment name; how can you get it from your pod? How do you get which namespace your pod has been deployed to? Or what about all the metadata we define as labels and annotations?

The good thing is that there is a way to get any single data we have commented on, so don’t worry; you will get all this information available to use if you need to.

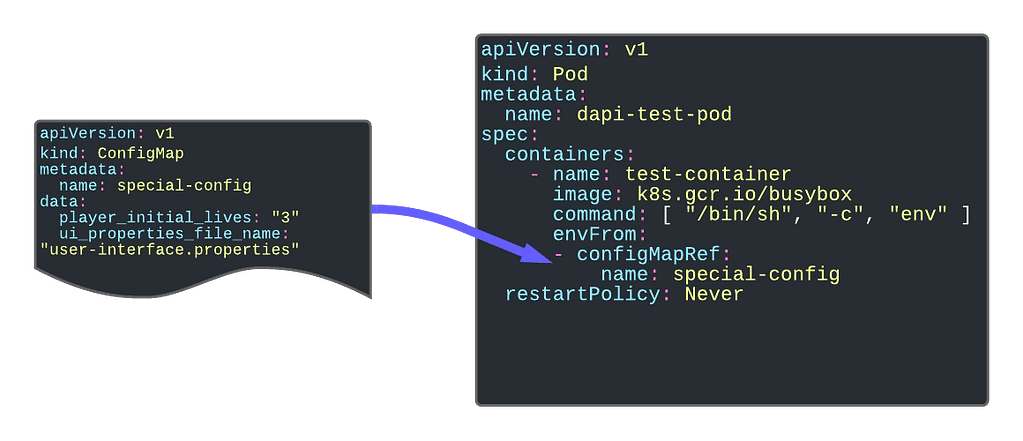

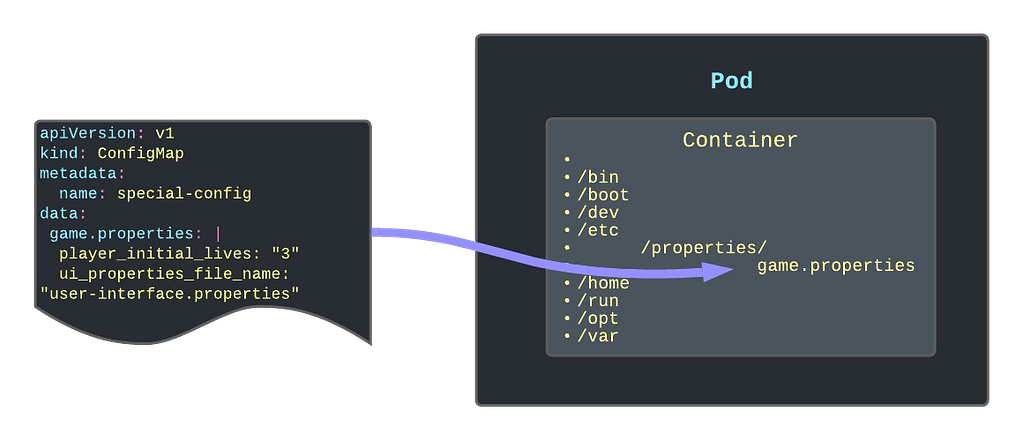

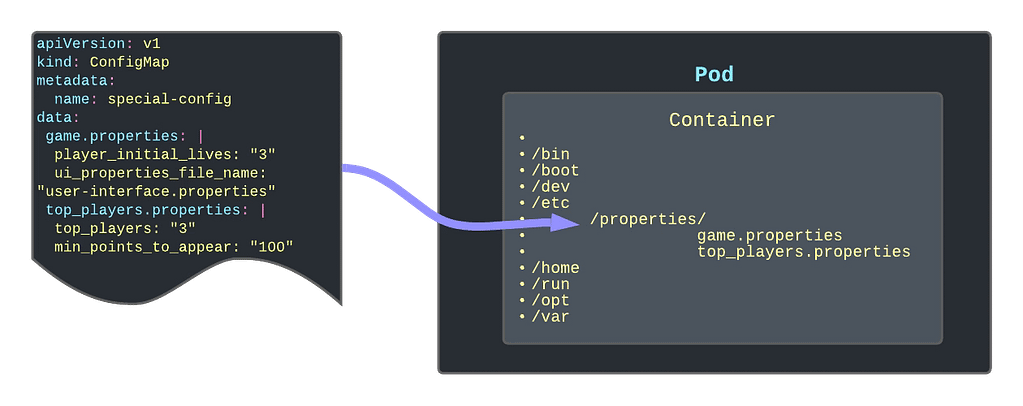

The standard way to access any information is through environment variables. This is the traditional way that we provide initial data to our pod. We already have seen we know we can use ConfigMaps to populate environment variables, but this is not the only way to provide data to our pods. There is much more, so take a look at it.

Discovering the fieldRef option

When we discussed using ConfigMap as environment variables, we had two ways to populate that information. Providing all the ConfigMap content, in which case we used the envFrom option, we can also use the valueFrom and provide the configMap name and the same key we would like to get the valueFrom.

So, following this section approach, we have an even more helpful command called fieldRef. fieldRef is the command name for a reference to a field, and we can use it inside the valueFrom directive. In a nutshell, we can provide a field reference as a value to an environment variable key.

So let’s take a look at the data that we can get from this object:

- metadata.name: This gets the pod name as a value for an environment value

- metadata.namespace: Provides the namespace that the pod is running as the value

- metadata.lables[LABELNAME]: Extract the value of the label as the value for the environment key

- metadata.annotations[ANNOTATIONNAME]: Extract the value of the annotation as value for the environment key

So here, you can see a snippet that defines different environment variables using this metadata as the value so you can use it inside the pod just gathering as standard environment variables:

env:

- name: APP_NAME

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.labels['app']

- name: DOMAIN_NAME

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.labels['domain']

- name: POD_NAMESPACE

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.namespace

- name: POD_NAME

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.name

Going Even Beyond

But this is not everything that the fieldRef option can provide, there is much more, and if you would like to take a look, you can do it here: