In the Kubernetes ecosystem, security and governance are key aspects that need continuous attention. While Kubernetes offers some out-of-the-box (OOTB) security features such as Pod Security Admission (PSA), these might not be sufficient for complex environments with varying compliance requirements. This is where Kyverno comes into play, providing a powerful yet flexible solution for managing and enforcing policies across your cluster.

In this post, we will explore the key differences between Kyverno and PSA, explain how Kyverno can be used in different use cases, and show you how to install and deploy policies with it. Although custom policy creation will be covered in a separate post, we will reference some pre-built policies you can use right away.

What is Pod Security Admission (PSA)?

Kubernetes introduced Pod Security Admission (PSA) as a replacement for the now deprecated PodSecurityPolicy (PSP). PSA focuses on enforcing three predefined levels of security: Privileged, Baseline, and Restricted. These levels control what pods are allowed to run in a namespace based on their security context configurations.

- Privileged: Minimal restrictions, allowing privileged containers and host access.

- Baseline: Applies standard restrictions, disallowing privileged containers and limiting host access.

- Restricted: The strictest level, ensuring secure defaults and enforcing best practices for running containers.

While PSA is effective for basic security requirements, it lacks flexibility when enforcing fine-grained or custom policies. We have a full article covering this topic that you can read here.

Kyverno vs. PSA: Key Differences

Kyverno extends beyond the capabilities of PSA by offering more granular control and flexibility. Here’s how it compares:

- Policy Types: While PSA focuses solely on security, Kyverno allows the creation of policies for validation, mutation, and generation of resources. This means you can modify or generate new resources, not just enforce security rules.

- Customizability: Kyverno supports custom policies that can enforce your organization’s compliance requirements. You can write policies that govern specific resource types, such as ensuring that all deployments have certain labels or that container images come from a trusted registry.

- Policy as Code: Kyverno policies are written in YAML, allowing for easy integration with CI/CD pipelines and GitOps workflows. This makes policy management declarative and version-controlled, which is not the case with PSA.

- Audit and Reporting: With Kyverno, you can generate detailed audit logs and reports on policy violations, giving administrators a clear view of how policies are enforced and where violations occur. PSA lacks this built-in reporting capability.

- Enforcement and Mutation: While PSA primarily enforces restrictions on pods, Kyverno allows not only validation of configurations but also modification of resources (mutation) when required. This adds an additional layer of flexibility, such as automatically adding annotations or labels.

When to Use Kyverno Over PSA

While PSA might be sufficient for simpler environments, Kyverno becomes a valuable tool in scenarios requiring:

- Custom Compliance Rules: For example, enforcing that all containers use a specific base image or restricting specific container capabilities across different environments.

- CI/CD Integrations: Kyverno can integrate into your CI/CD pipelines, ensuring that resources comply with organizational policies before they are deployed.

- Complex Governance: When managing large clusters with multiple teams, Kyverno’s policy hierarchy and scope allow for finer control over who can deploy what and how resources are configured.

If your organization needs a more robust and flexible security solution, Kyverno is a better fit compared to PSA’s more generic approach.

Installing Kyverno

To start using Kyverno, you’ll need to install it in your Kubernetes cluster. This is a straightforward process using Helm, which makes it easy to manage and update.

Step-by-Step Installation

Add the Kyverno Helm repository:

helm repo add kyverno https://kyverno.github.io/kyverno/Update Helm repositories:

helm repo updateInstall Kyverno in your Kubernetes cluster:

helm install kyverno kyverno/kyverno --namespace kyverno --create-namespaceVerify the installation:

kubectl get pods -n kyvernoAfter installation, Kyverno will begin enforcing policies across your cluster, but you’ll need to deploy some policies to get started.

Deploying Policies with Kyverno

Kyverno policies are written in YAML, just like Kubernetes resources, which makes them easy to read and manage. You can find several ready-to-use policies from the Kyverno Policy Library, or create your own to match your requirements.

Here is an example of a simple validation policy that ensures all pods use trusted container images from a specific registry:

apiVersion: kyverno.io/v1

kind: ClusterPolicy

metadata:

name: require-trusted-registry

spec:

validationFailureAction: enforce

rules:

- name: check-registry

match:

resources:

kinds:

- Pod

validate:

message: "Only images from 'myregistry.com' are allowed."

pattern:

spec:

containers:

- image: "myregistry.com/*"This policy will automatically block the deployment of any pod that uses an image from a registry other than myregistry.com.

Applying the Policy

To apply the above policy, save it to a YAML file (e.g., trusted-registry-policy.yaml) and run the following command:

kubectl apply -f trusted-registry-policy.yamlOnce applied, Kyverno will enforce this policy across your cluster.

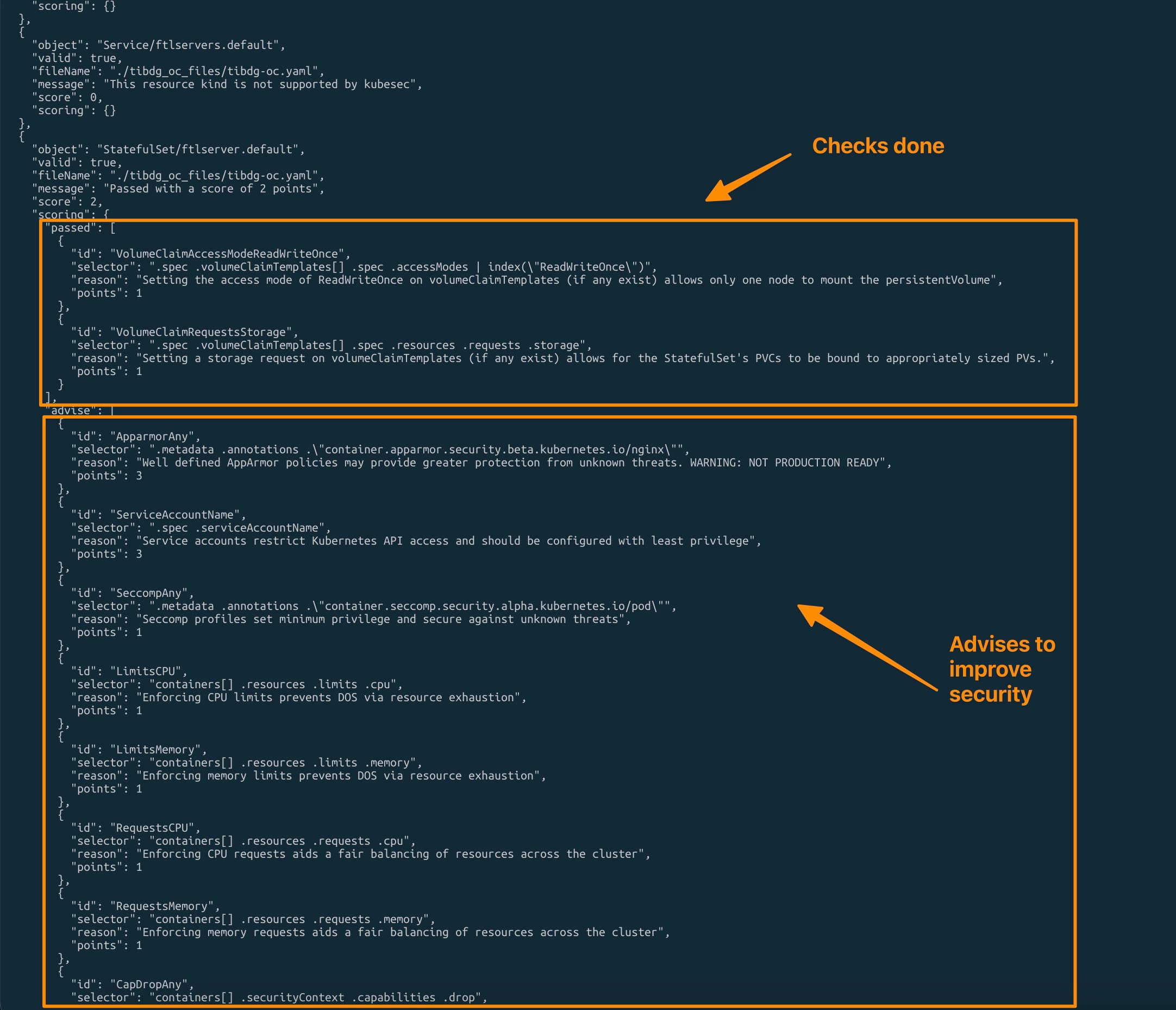

Viewing Kyverno Policy Reports

Kyverno generates detailed reports on policy violations, which are useful for audits and tracking policy compliance. To check the reports, you can use the following commands:

List all Kyverno policy reports:

kubectl get clusterpolicyreportDescribe a specific policy report to get more details:

kubectl describe clusterpolicyreport <report-name>These reports can be integrated into your monitoring tools to trigger alerts when critical violations occur.

Conclusion

Kyverno offers a flexible and powerful way to enforce policies in Kubernetes, making it an essential tool for organizations that need more than the basic capabilities provided by PSA. Whether you need to ensure compliance with internal security standards, automate resource modifications, or integrate policies into CI/CD pipelines, Kyverno’s extensive feature set makes it a go-to choice for Kubernetes governance.

For now, start with the out-of-the-box policies available in Kyverno’s library. In future posts, we’ll dive deeper into creating custom policies tailored to your specific needs.

📚 Want to dive deeper into Kubernetes? This article is part of our comprehensive Kubernetes Architecture Patterns guide, where you’ll find all fundamental and advanced concepts explained step by step.