Telepresence is the way to reduce the time between your lines of code and a cloud-native workload running.

We all know how cloud-native workloads and Kubernetes have changed how we do things. There are a lot of benefits that come with the effect of containerization and orchestration platforms such as Kubernetes, and we have discussed a lot about it: scalability, self-healing, auto-discovery, resilience, and so on.

But some challenges have been raised, most of them on the operational aspect that we have a lot of projects focused on tackling, but usually, we forget about what the ambassador has defined as the “inner dev cycle.”

The “inner dev cycle” is the productive workflow that each developer follows when working on a new application, service, or component. This iterative flow is where we code, test what we’ve coded, and fix what is not working or improve what we already have.

This flow has existed since the beginning of time; it doesn’t matter if you were coding in C using STD Library or COBOL in the early 1980 or doing nodejs with the latest frameworks and libraries at your disposal.

We have seen movements towards making this inner cycle more effective, especially in front-end development. We have many options to see the last change we have done in code, just saving the file. But for the first time when the movement to a container-based platform, this flow makes devs less productive.

The main reason is that the number of tasks a dev needs to do has increased. Imagine this set of steps that we need to perform:

- Build the app

- Build the container image

- Deploy the container image in Kubernetes

These actions are not as fast as testing your changes locally, making devs less productive than before, which is what the “telepresence” project is trying to solve.

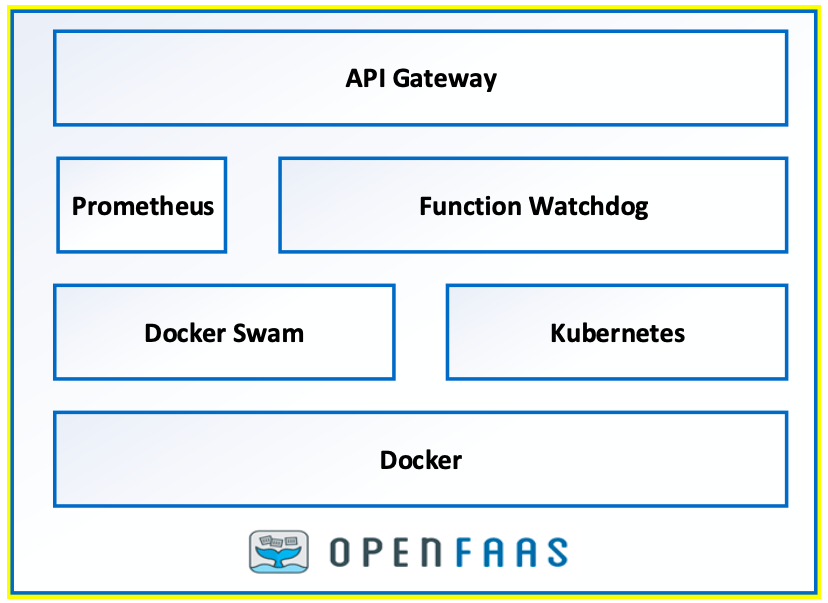

Telepresence is an incubator project from the CNCF that has recently focused a lot of attention because it has included OOTB in the latest releases of the Docker Desktop component. Based on its own words, this is the definition of the telepresence project:

Telepresence is an open-source tool that lets developers code and test microservices locally against a remote Kubernetes cluster. Telepresence facilitates more efficient development workflows while relieving the need to worry about other service dependencies.

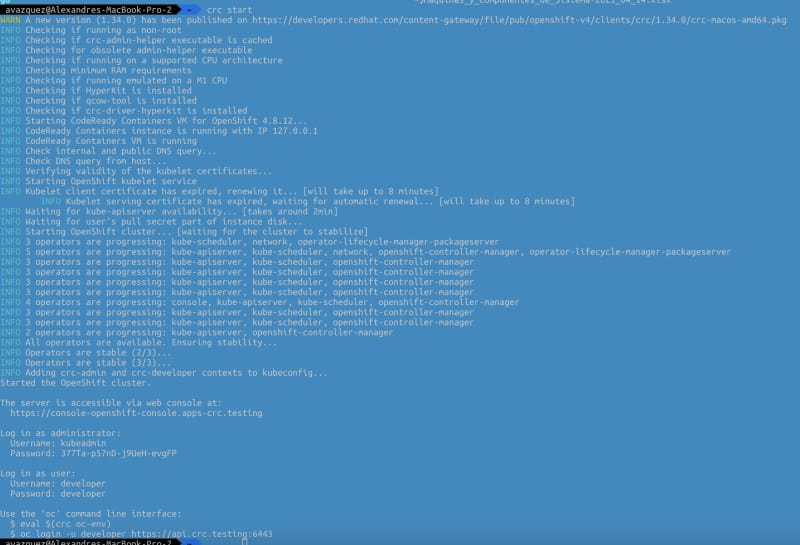

Ok, so let’s see how we can start? Let’s dive in together. The first thing we need to do is to install telepresence in our Kubernetes cluster:

Note: It is also a way to install telepresence using Helm in your cluster following these steps:

helm repo add datawire https://app.getambassador.io

helm repo update

kubectl create namespace ambassador

helm install traffic-manager --namespace ambassador datawire/telepresence

Now I will create a simple container that will host a Golang application that exposes a simple REST service and make it more accessible; I will follow the tutorial that is available below; you can do it as well.

and the Gin Web Framework (Gin).

Once we have our golang application ready, we are going to generate the container from it, using the following Dockerfile:

FROM golang:latest

RUN apt-get update

RUN apt-get upgrade -y

ENV GOBIN /go/bin

WORKDIR /app

COPY *.go ./

RUN go env -w GO111MODULE=off

RUN go get .

RUN go build -o /go-rest

EXPOSE 8080

CMD [ "/go-rest" ]

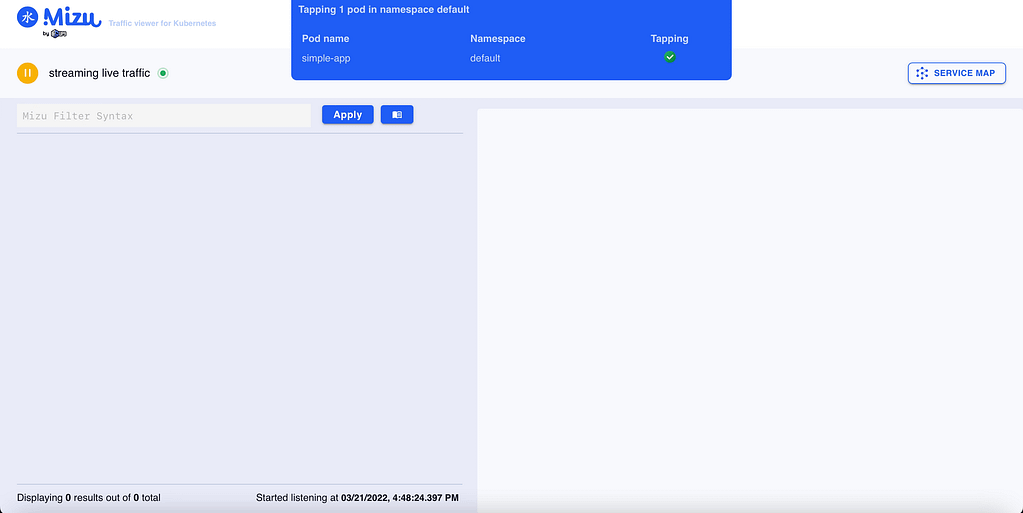

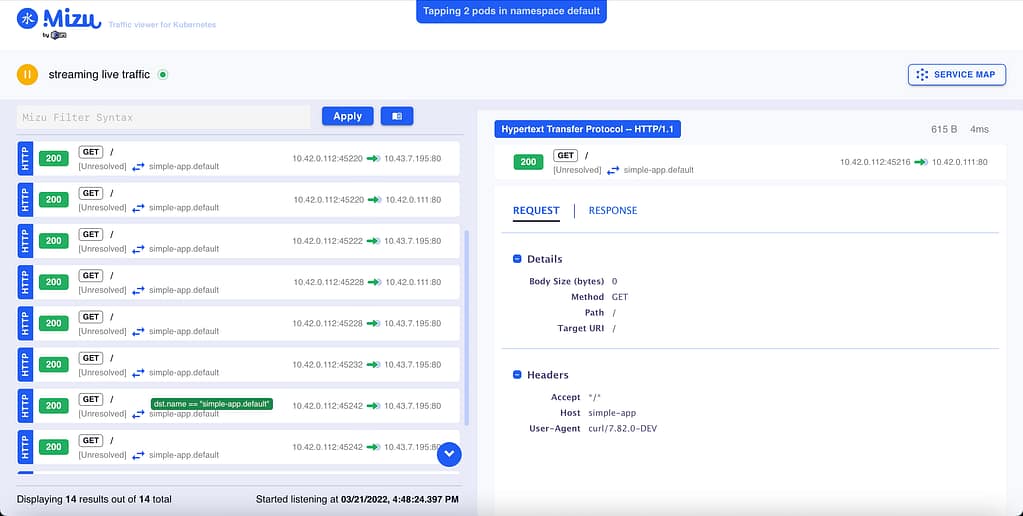

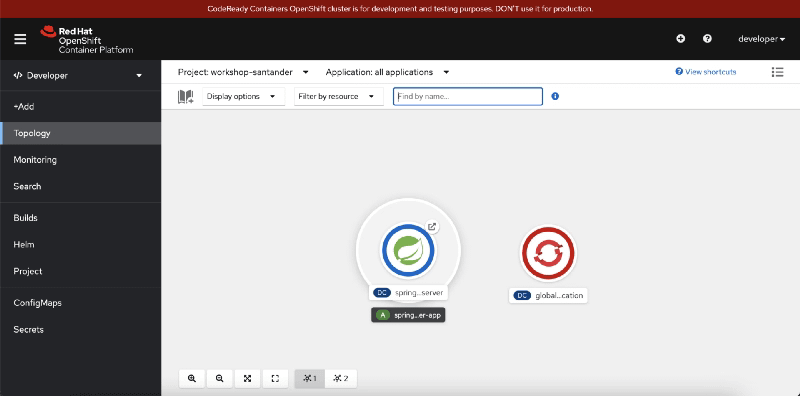

Then once we have the app, we’re going to upload to the Kubernetes server and run it as a deployment, as you can see in the picture below:

kubectl create deployment rest-service --image=quay.io/alexandrev/go-test --port=8080

kubectl expose deploy/rest-service

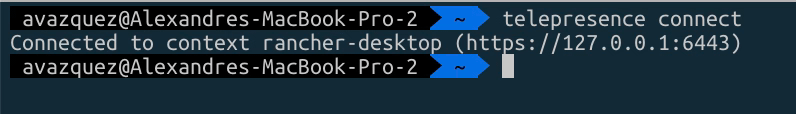

Once we have that, it is the moment to start executing the telepresence, and we will start connecting to the cluster using the following command telepresence connect, and it will show an output like this one:

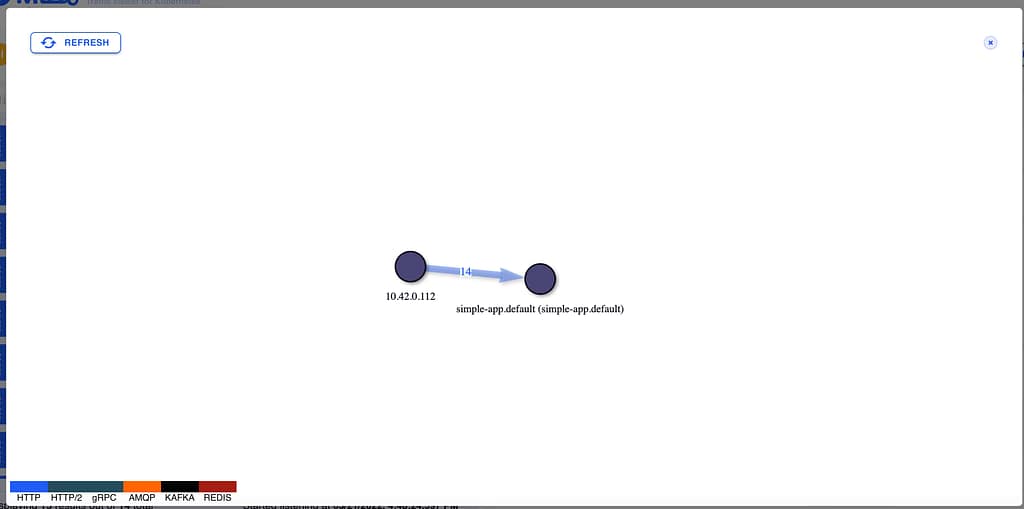

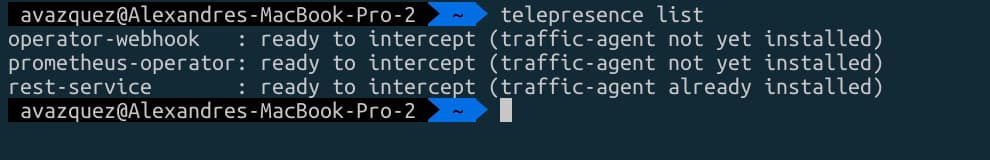

Then we are going to list the endpoints available to intercept with the command telepresence listand we will see our rest-service that we have exposed before:

Now, we will run the specific interceptor, but before that, we’re going to do the trick so we can connect it to our Visual Studio Code. We will generate a launch.json file in Visual Studio Code with the following content:

{

// Use IntelliSense to learn about possible attributes.

// Hover to view descriptions of existing attributes.

// For more information, visit: https://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?linkid=830387

"version": "0.2.0",

"configurations": [

{

"name": "Launch with env file",

"type": "go",

"request": "launch",

"mode": "debug",

"program": "1",

"envFile": "NULL/go-debug.env"

}

]

}

The interesting part here is the envFile argument that points to a non-existent file go-debug.env on the same folder, so we need to make sure that we generate that file when we do the interception. So we will use the following command:

telepresence intercept rest-service --port 8080:8080 --env-file /Users/avazquez/Data/Projects/GitHub/rest-golang/go-debug.env

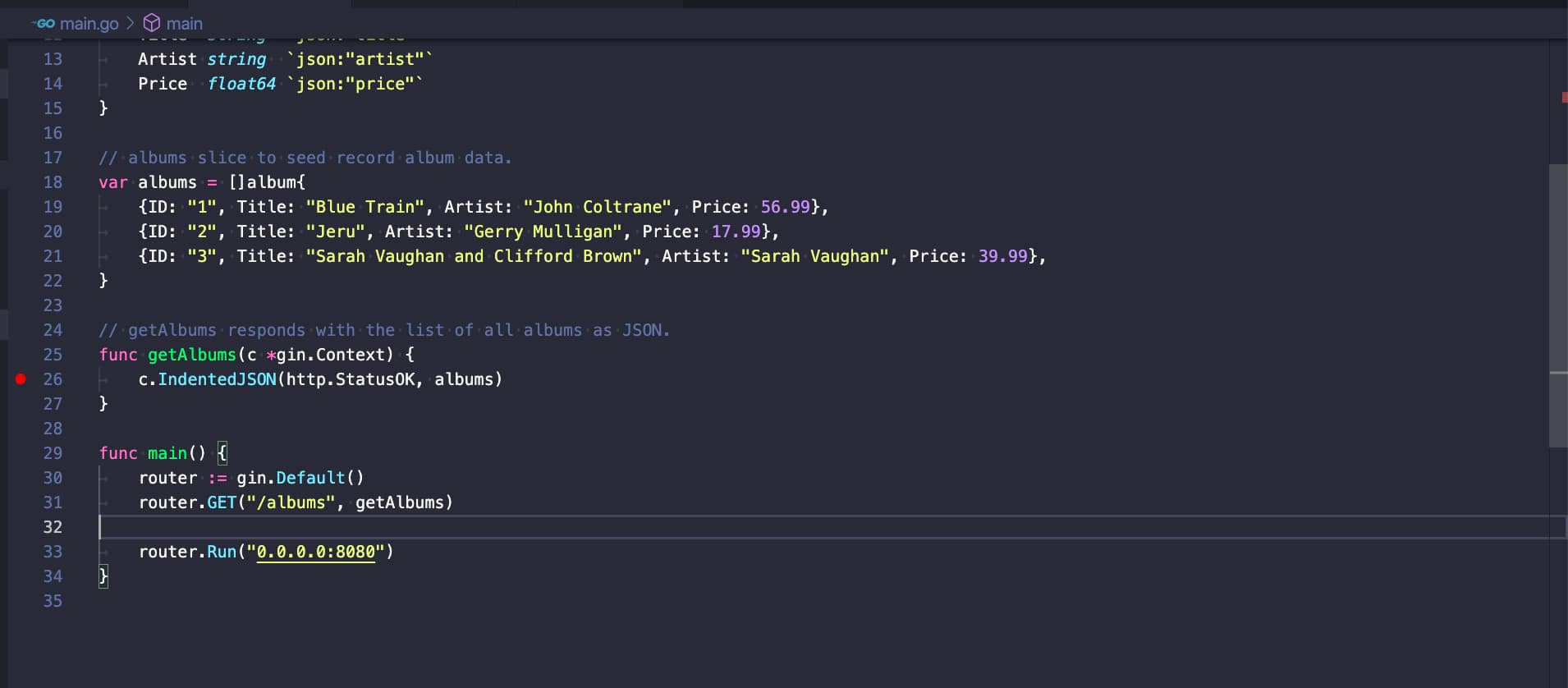

And now, we can start our debug session in Visual Studio code and maybe add a breakpoint and some lines, as you can see in the picture below:

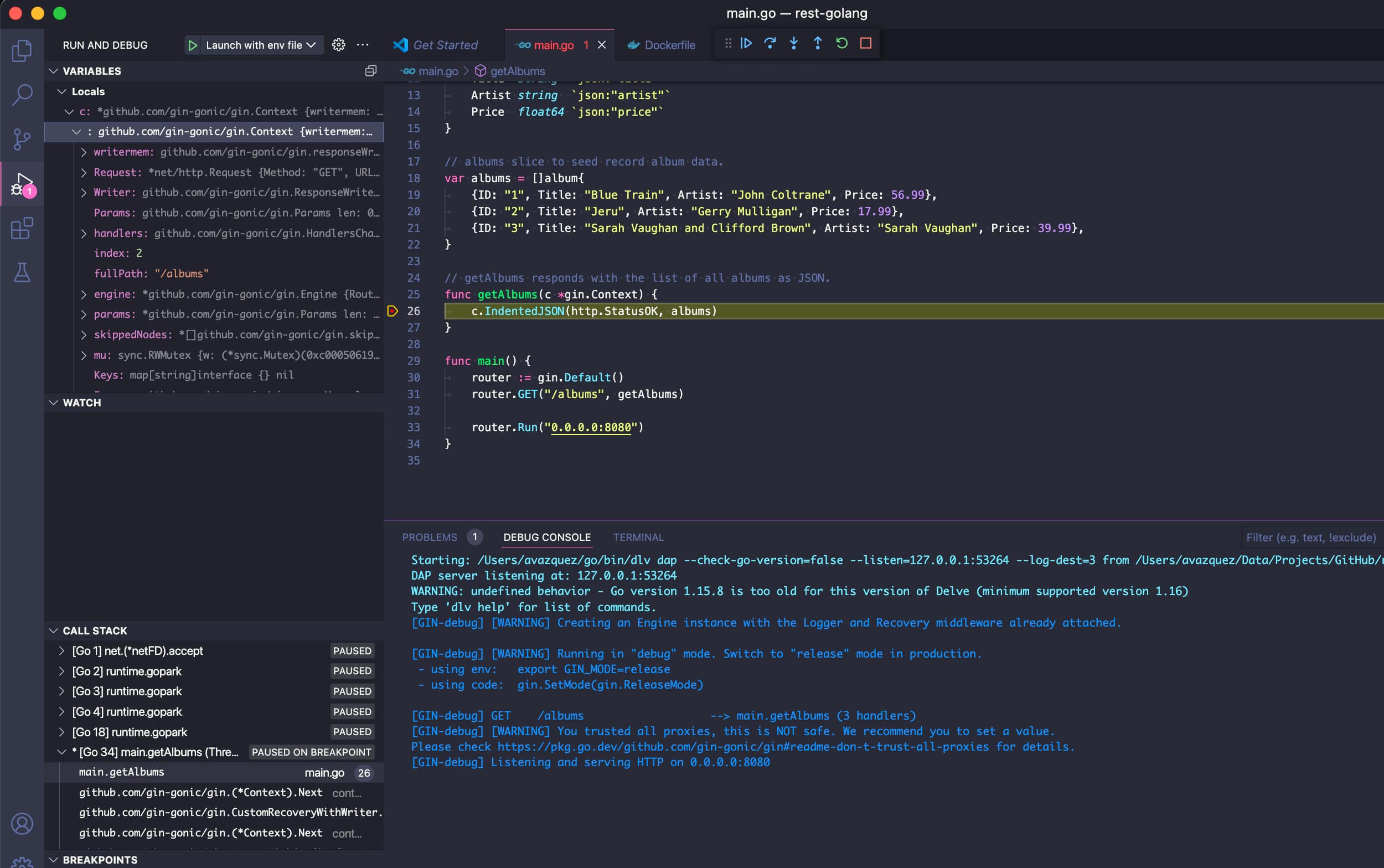

So, now, if we hit the pod in Kubernetes, we will see how the breakpoint is being reached as we were in a local debugging session.

That means that we can inspect variables and everything, change the code, or do whatever we need to speed up our development!

📚 Want to dive deeper into Kubernetes? This article is part of our comprehensive Kubernetes Architecture Patterns guide, where you’ll find all fundamental and advanced concepts explained step by step.