Helm Templates in Files, such as ConfigMaps Content or Secrets Content, is of the most common requirements when you are in the process of creating a new helm chart. As you already know, Helm Chart is how we use Kubernetes to package our application resources and YAML in a single component that we can manage at once to ease the maintenance and operation process.

Helm Templates Overview

By default, the template process works with YAML files, allowing us to use some variables and some logic functions to customize and templatize our Kubernetes YAML resources to our needs.

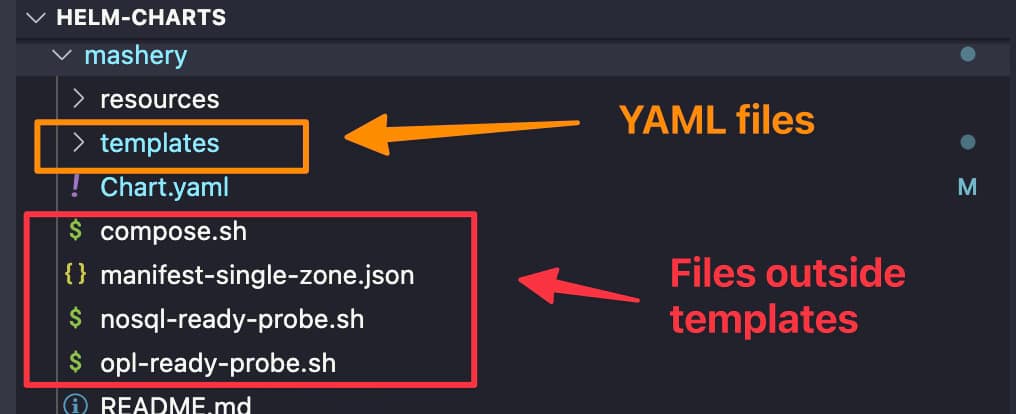

So, in a nutshell, we can only have yaml files inside the templates folder of a YAML. But sometimes we would like to do the same process on ConfigMaps or Secrets or to be more concrete to the content of those ConfigMaps, for example, properties files and so on.

As you can see it is quite normal to have different files such as json configuration file, properties files, shell scripts as part of your helm chart, and most of the times you would like to give some dynamic approach to its content, and that’s why using helm Templates in Files it is so important to be the main focus for this article

Helm Helper Functions to Manage Files

By default, Helm provides us with a set of functions to manage files as part of the helm chart to simplify the process of including them as part of the chart, such as the content of ConfigMap or Secret. Some of these functions are the following:

- .Files.Glob: This function allows to find any pattern of internal files that matches the pattern, such as the following example:

{ range $path, $ := .Files.Glob ".yaml" } - .Files.Get: This is the simplest option to gather the content of a specific file that you know the full path inside your helm chart, such as the following sample:

{{ .Files.Get "config1.toml" | b64enc }}

You can even combine both functions to use together such as in the following sample:

{{ range $path, $_ := .Files.Glob "**.yaml" }}

{{ $.Files.Get $path }}

{{ end }}

Then you can combine that once you have the file that you want to use with some helper functions to easily introduce in a ConfigMap and a Secret as explained below:

- .AsConfig : Use the file content to be introduced as ConfigMap handling the pattern:

file-name: file-content - .AsSecrets: Similar to the previous one, but doing the base64 encoding for the data.

Here you can see a real example of using this approach in an actual helm chart situation:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: zones-property

namespace: {{ $.Release.Namespace }}

data:

{{ ( $.Files.Glob "tml_zones_properties.json").AsSecrets | indent 2 }}

You can find more information about that here. But this only allows us to grab the file as is and include it in a ConfigMap. It is not allowing us to do any logic or any substitution to the content as part of that process. So, if we want to modify this, this is not a valid sample.

How To Use Helm Templates in Files Such as ConfigMaps or Secrets?

In case we can do some modifications to the content, we need to use the following formula:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: papi-property

namespace: {{ $.Release.Namespace }}

data:

{{- range $path, $bytes := .Files.Glob "tml_papi_properties.json" }}

{{ base $path | indent 2 }}: {{ tpl ($.Files.Get $path) $ | b64enc }}

{{ end }}

So, here we are doing is first iterating for the files that match the pattern using the .Files.Glob function we explained before, iterating in case we have more than one. Then we manually create the structure following the pattern : file-name: file-content.

To do that, we use the function base to provide just the filename from a full path (and add the proper indentation) and then use the .Files.Get to grab the file’s content and do the base64 encoding using the b64encfunction because, in this case, we’re handling a secret.

The trick here is adding the tpl function that allows this file’s content to go through the template process; this is how all the modifications that we need to do and the variables referenced from the .Values object will be adequately replaced, giving you all the power and flexibility of the Helm Chart in text files such as properties, JSON files, and much more.

I hope this is as useful for you as it has been for me in creating new helm charts! And Look here for other tricks using loops or dependencies.