In the previous article, we described what capability BanzaiCloud Logging Operator provides and its main features. So, today we are going to see how we can implement it.

The first thing we need to do is to install the operator itself, and to do that, we have a helm chart at our disposal, so the only thing that we will need to do are the following commands:

helm repo add banzaicloud-stable https://kubernetes-charts.banzaicloud.com

helm upgrade --install --wait --create-namespace --namespace logging logging-operator banzaicloud-stable/logging-operator

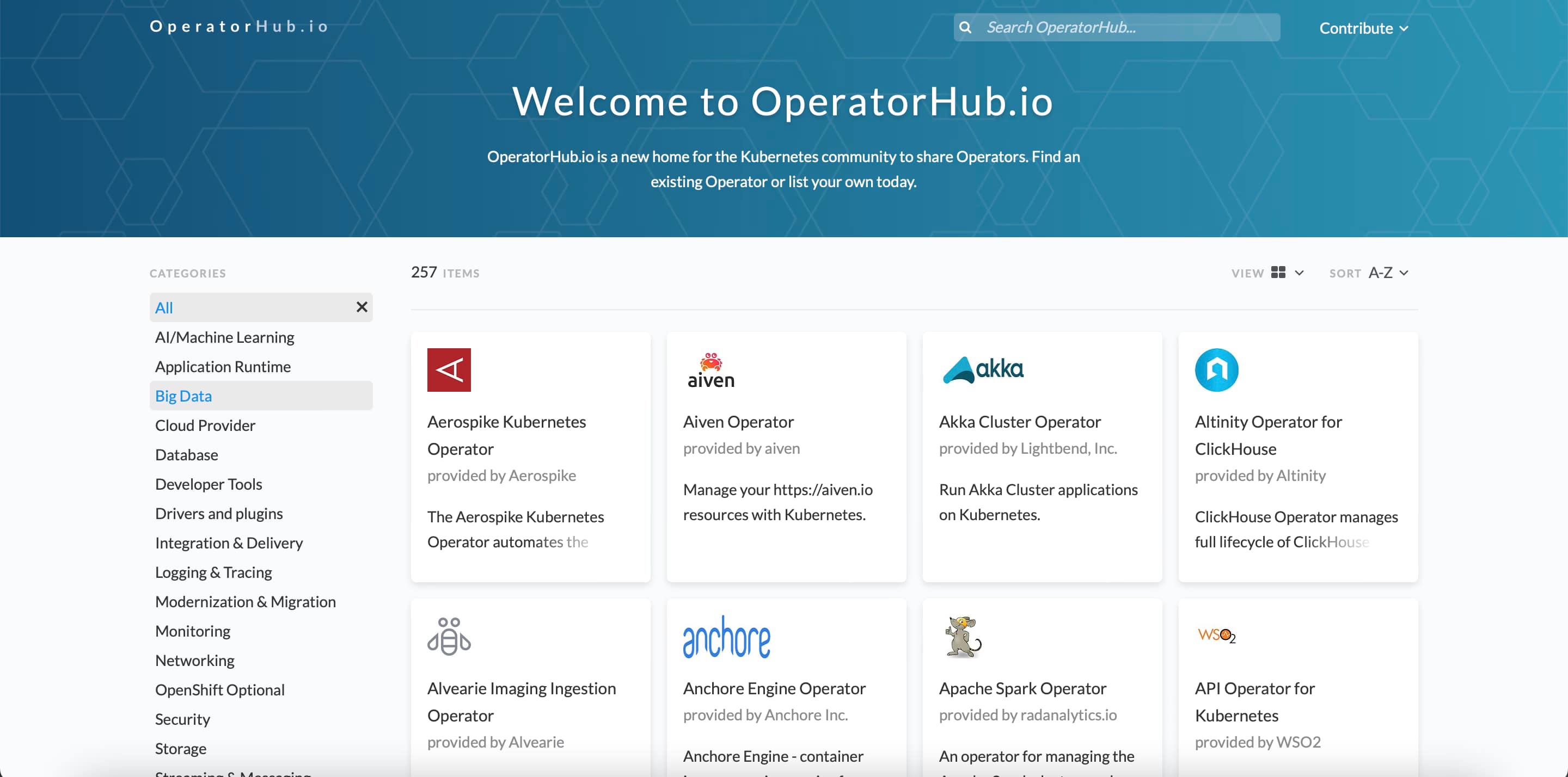

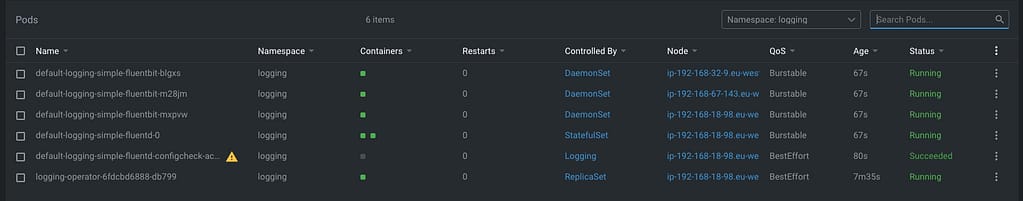

That will create a logging namespace (in case you didn’t have it yet), and it will deploy the operator components itself, as you can see in the picture below:

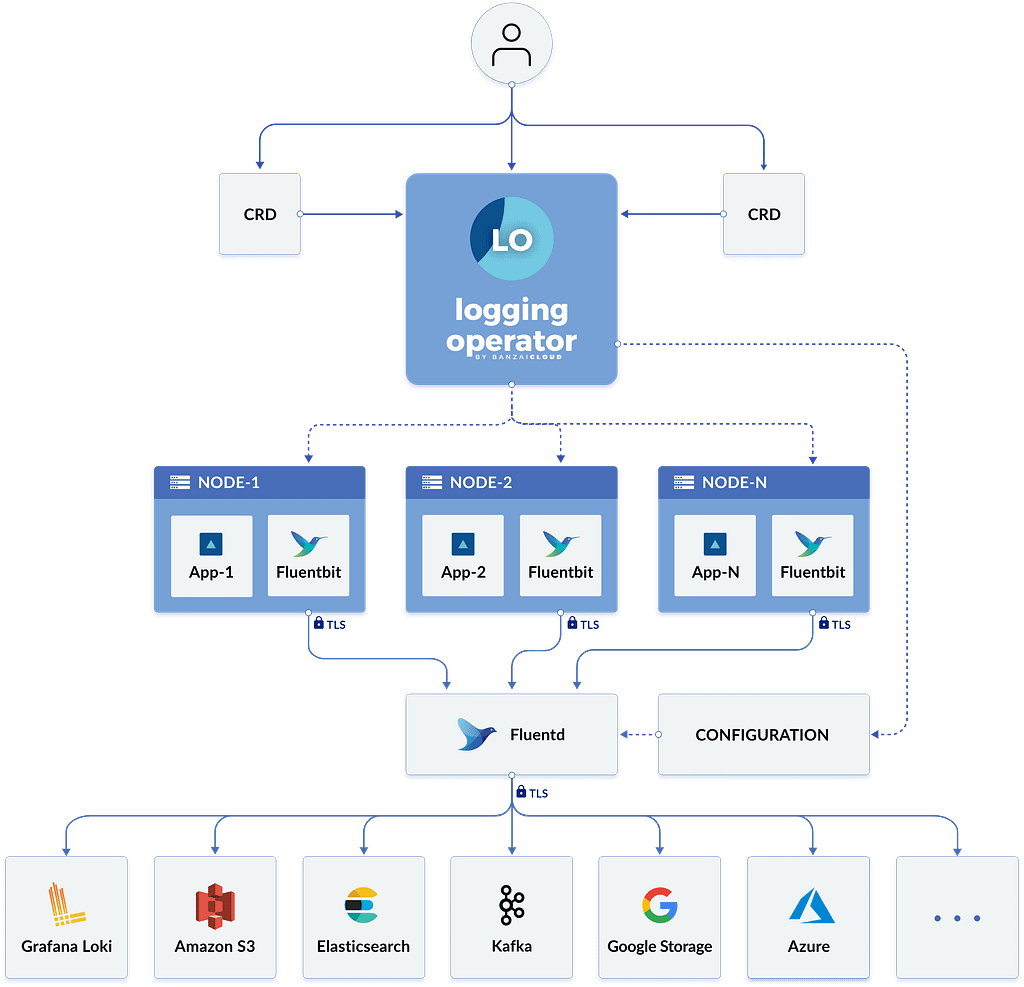

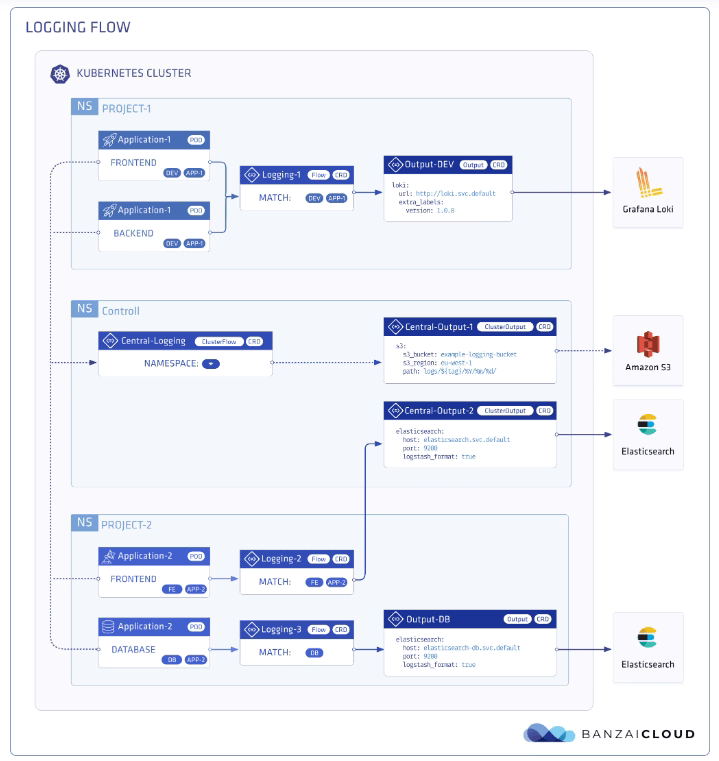

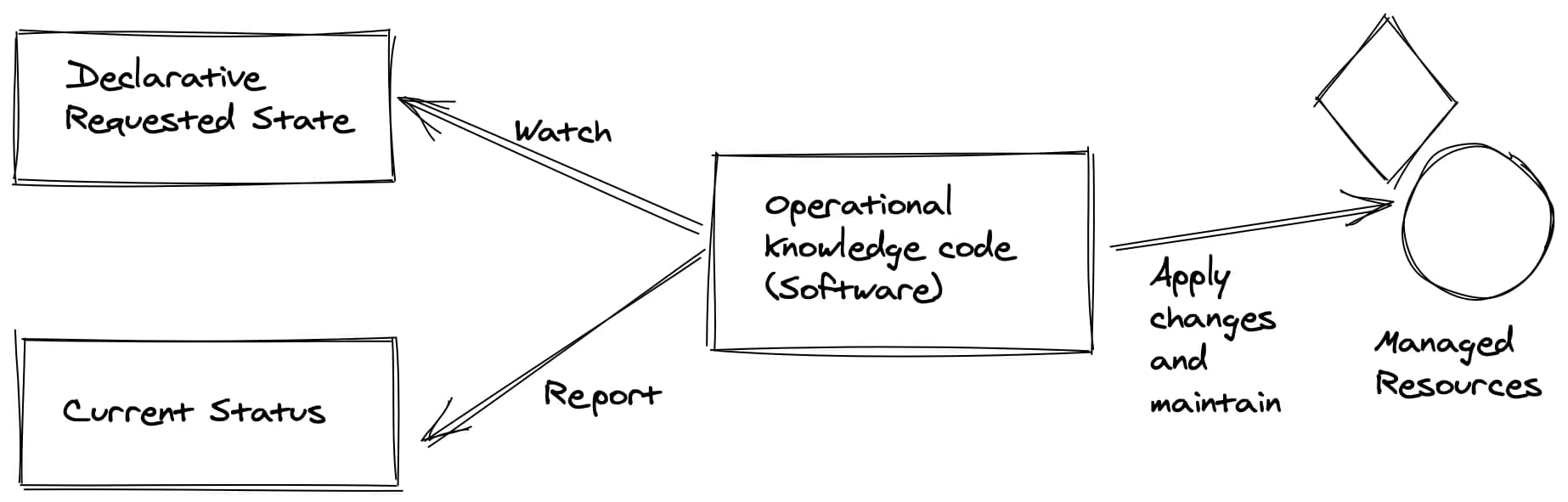

So, now we can start creating the resources we need using the CRD that we commented on in the previous article but to do a recap. These are the ones that we have at our disposal:

- logging – The logging resource defines the logging infrastructure for your cluster that collects and transports your log messages. It also contains configurations for Fluentd and Fluent-bit.

- output / clusteroutput – Defines an Output for a logging flow, where the log messages are sent. output will be namespaced based, and clusteroutput will be cluster based.

- flow / clusterflow – Defines a logging flow using filters and outputs. The flow routes the selected log messages to the specified outputs. flow will be namespaced based, and clusterflows will be cluster based.

So, first of all, we are going to define our scenario. I don’t want to make something complex; I wish that all the logs that my workloads generate, no matter what namespace they are in, are sent to a Grafana Loki instance that I have also installed on that Kubernetes Cluster on a specific endpoint using the Simple Scalable configuration for Grafana Loki.

So, let’s start with the components that we need. First, we need a Logging object to define my Logging infrastructure, and I will create it with the following command.

kubectl -n logging apply -f - <<"EOF"

apiVersion: logging.banzaicloud.io/v1beta1

kind: Logging

metadata:

name: default-logging-simple

spec:

fluentd: {}

fluentbit: {}

controlNamespace: logging

EOF

We will keep the default configuration for fluentd and fluent-bit just for the sake of the sample, and later on in upcoming articles, we can talk about a specific design, but that’s it.

Once the CRD is processed, the components will appear on your logging namespace. In my case that I’m using a 3-node cluster, I will see 3 instances for fluent-bit deployed as a DaemonSet and a single example of fluentd, as you can see in the picture below:

So, now we need to define the communication with Loki, and as I would like to use this for any namespace I can have on my cluster, I will use the ClusterOutput option instead of the normal Output one that is namespaced based. And to do that, we will use the following command (please ensure that the endpoint is the right one; in our case, this is loki-gateway. default as it is running inside the Kubernetes Cluster:

kubectl -n logging apply -f - <<"EOF"

apiVersion: logging.banzaicloud.io/v1beta1

kind: ClusterOutput

metadata:

name: loki-output

spec:

loki:

url: http://loki-gateway.default

configure_kubernetes_labels: true

buffer:

timekey: 1m

timekey_wait: 30s

timekey_use_utc: true

EOF

And pretty much we have everything; we just need one flow to communicate our Logging configuration to the ClusterOutput we just created. And again, we will go with the ClusterFlow because we would like to define this at the Cluster level and not in a by-namespaced fashion. So we will use the following command:

kubectl -n logging apply -f - <<"EOF"

apiVersion: logging.banzaicloud.io/v1beta1

kind: ClusterFlow

metadata:

name: loki-flow

spec:

filters:

- tag_normaliser: {}

match:

- select: {}

globalOutputRefs:

- loki-output

EOF

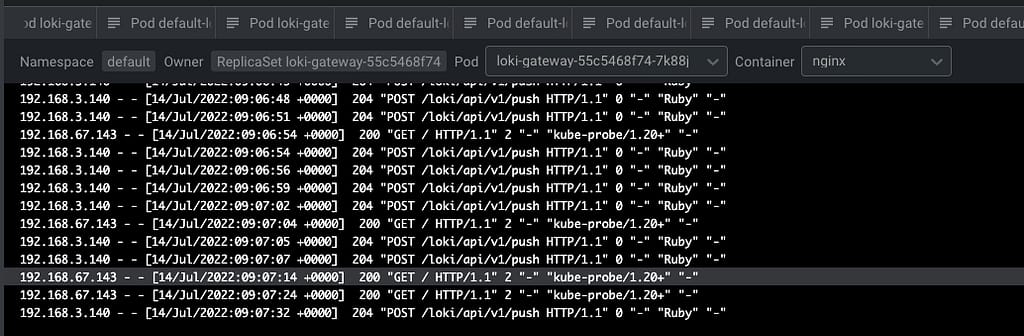

And after some time to do the reload of the configuration (1-2 minutes or so), you will start to see in the Loki traces something like this:

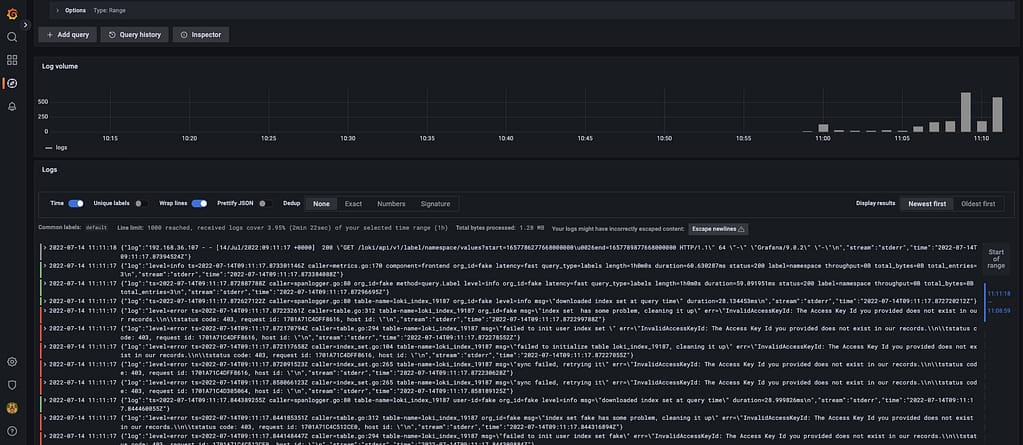

And that indicates that we are already receiving push of logs from the different components, mainly the fluentd element we configured in this case. But I think it is better to see it graphically with Grafana:

And that’s it! And to change our logging configuration is as simple as changing the CRD component we defined, applying matches and filters, or sending it to a new place. Straightforwardly we have this completely managed.

📚 Want to dive deeper into Kubernetes? This article is part of our comprehensive Kubernetes Architecture Patterns guide, where you’ll find all fundamental and advanced concepts explained step by step.