Grafana Loki is becoming one of the de-facto standards for log aggregation in Kubernetes workloads nowadays, and today, we are going to show how we can use together Grafana Loki and MinIO. We already have covered on several occasions the capabilities of Grafana Loki that have emerged as the main alternative to the Elasticsearch leadership in the last 5-10 years for log aggregation.

With a different approach, more lightweight, more cloud-native, more focus on the good things that Prometheus has provided but for logs and with the sponsorship of a great company such as Grafana Labs with the dashboard tools as the leader of each day more enormous stack of tools around the observability world.

And also, we already have covered MinIO as an object store that can be deployed anywhere. It’s like having your S3 service on whatever cloud you like or on-prem. So today, we are going to see how both can work together.

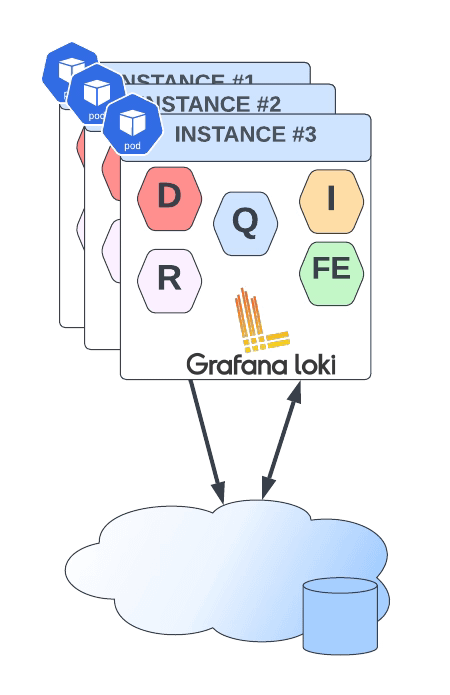

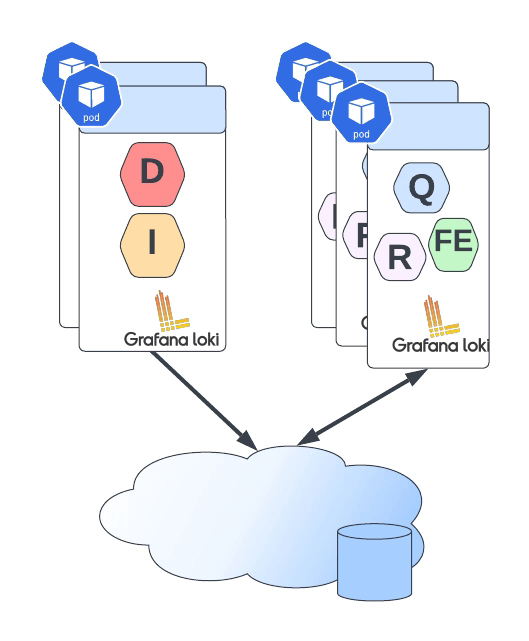

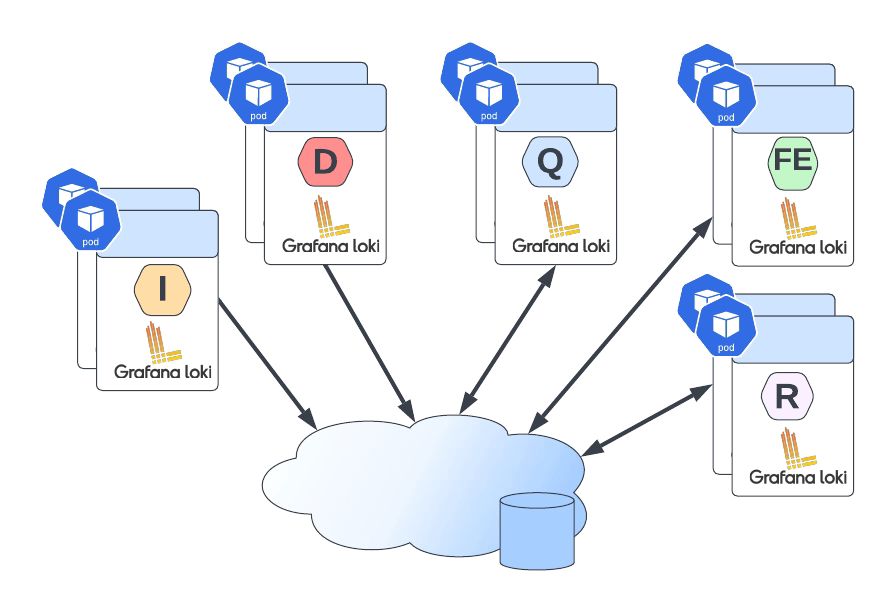

Grafana Loki mainly supports three deployment models: monolith, simple-scalable, and distributed. Pretty much everything but monolith has the requirement to have an Object Storage solution to be able to work on a distributed scalable mode. So, if you have your deployment in AWS, you already have covered with S3. Also, Grafana Loki supports most of the Object Storage solutions for the cloud ecosystem of the leading vendors. Still, the problem comes when you would like to rely on Grafana Loki for a private cloud or on-premises installation.

In that case, is where we can rely on MinIO. To be honest, you can use MinIO also in the cloud world to have a more flexible and transparent solution and avoid any lock-in with a cloud vendor. Still, for on-premises, its uses have become mandatory. One of the great features of MinIO is that it implements the S3 API, so pretty much anything that supports S3 will work with MinIO.

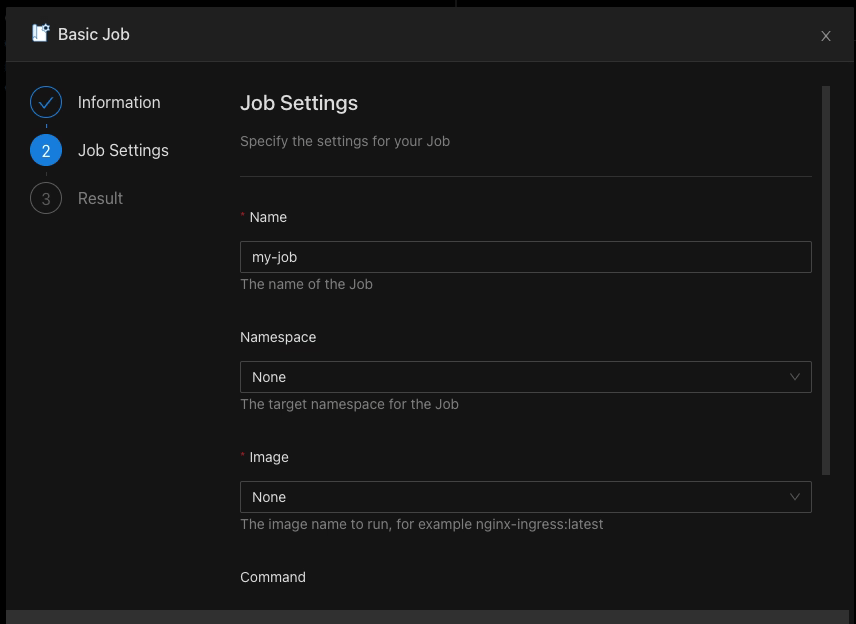

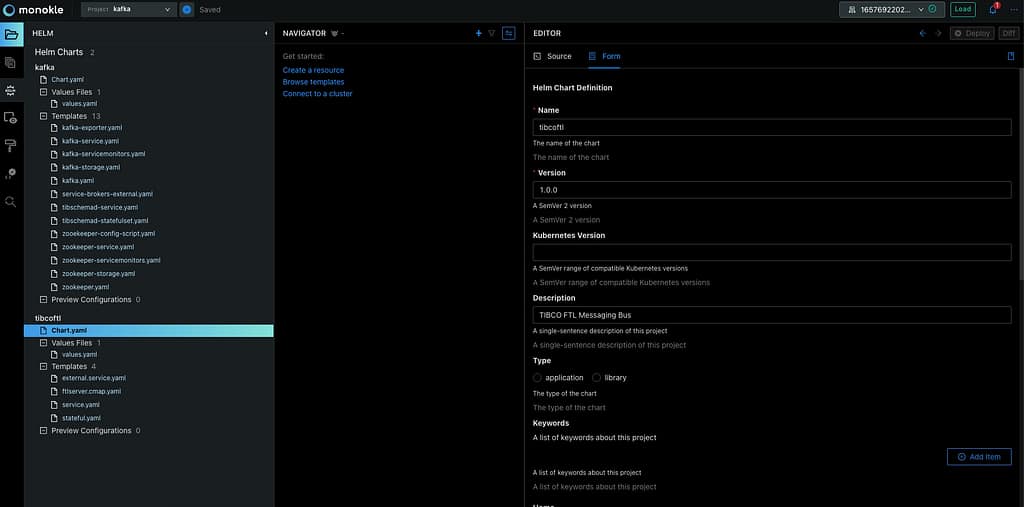

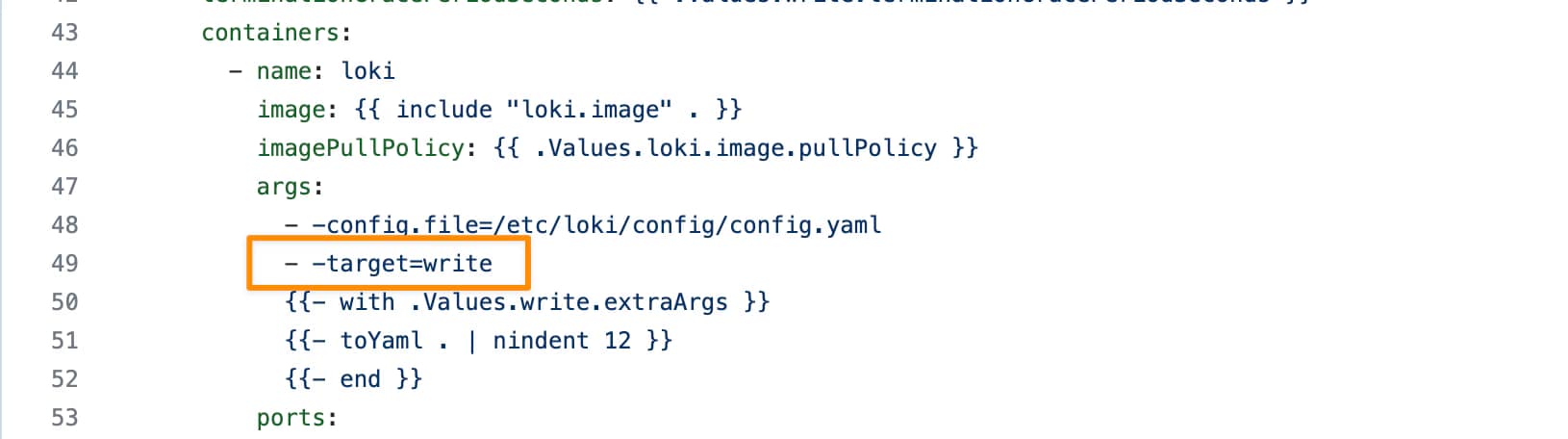

In this case, I just need to adapt some values on the helm chart from Loki in the simple-distributed mode as shown below:

loki:

storage:

s3:

s3: null

endpoint: http://minio.minio:9000

region: null

secretAccessKey: XXXXXXXXXXX

accessKeyId: XXXXXXXXXX

s3ForcePathStyle: true

insecure: true

We’re just pointing to the endpoint from our MinIO tenant, in our case, also deployed on Kubernetes on port 9000. We’re also providing the credentials to connect and finally just showing that needs s3ForcePathSyle: true is required for the endpoint to be transformed to minio.minio:9000/bucket instead to bucket.minio.minio:9000, so it will work better on a Kubernetes ecosystem.

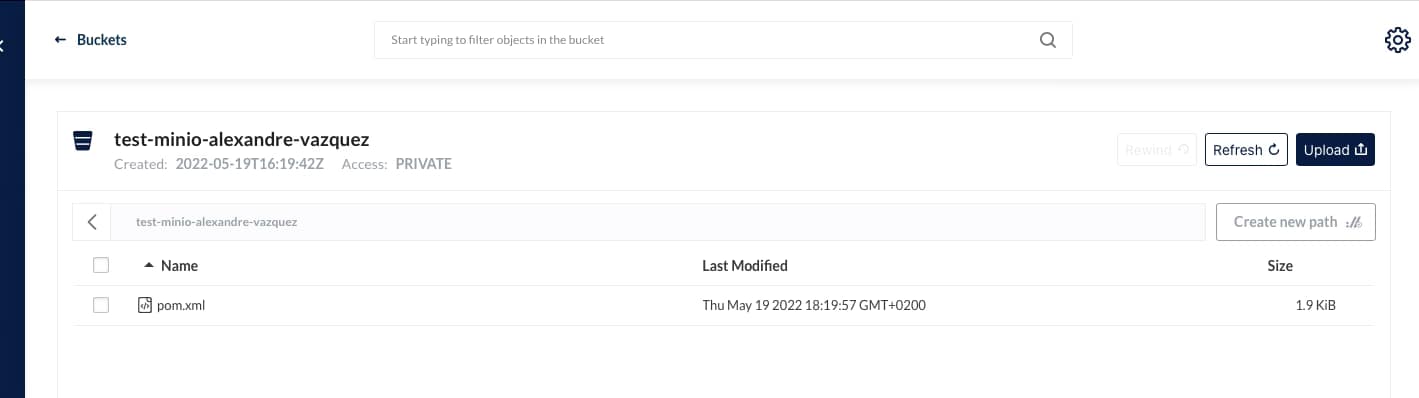

And that’s pretty much it; as soon as you start it, you will begin to see that the buckets are starting to be populated as they will do in case you were using S3, as you can see in the picture below:

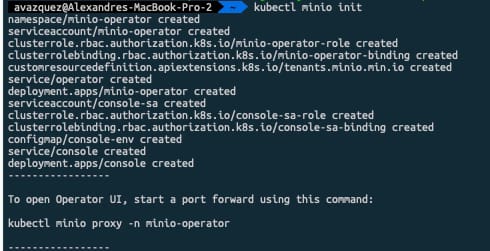

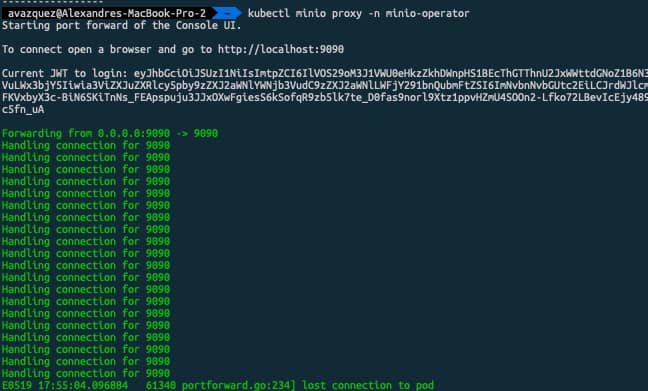

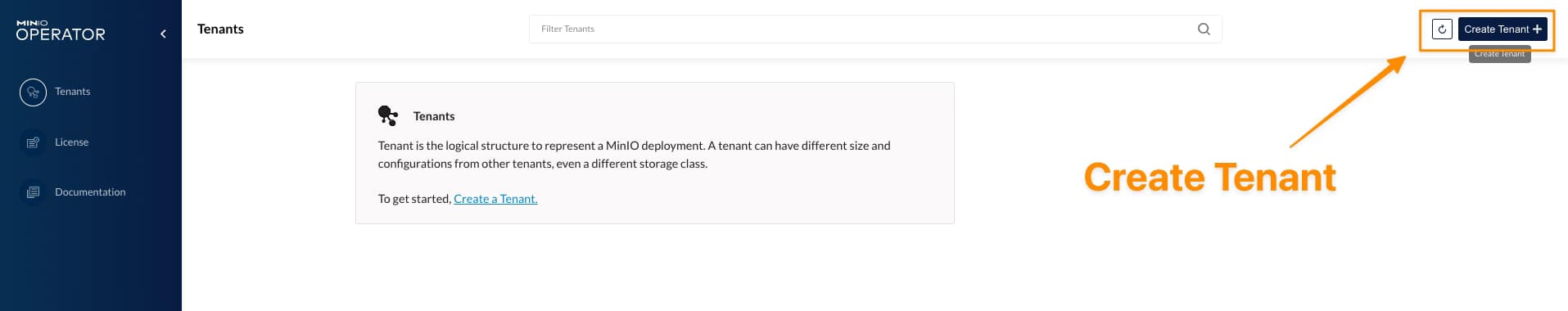

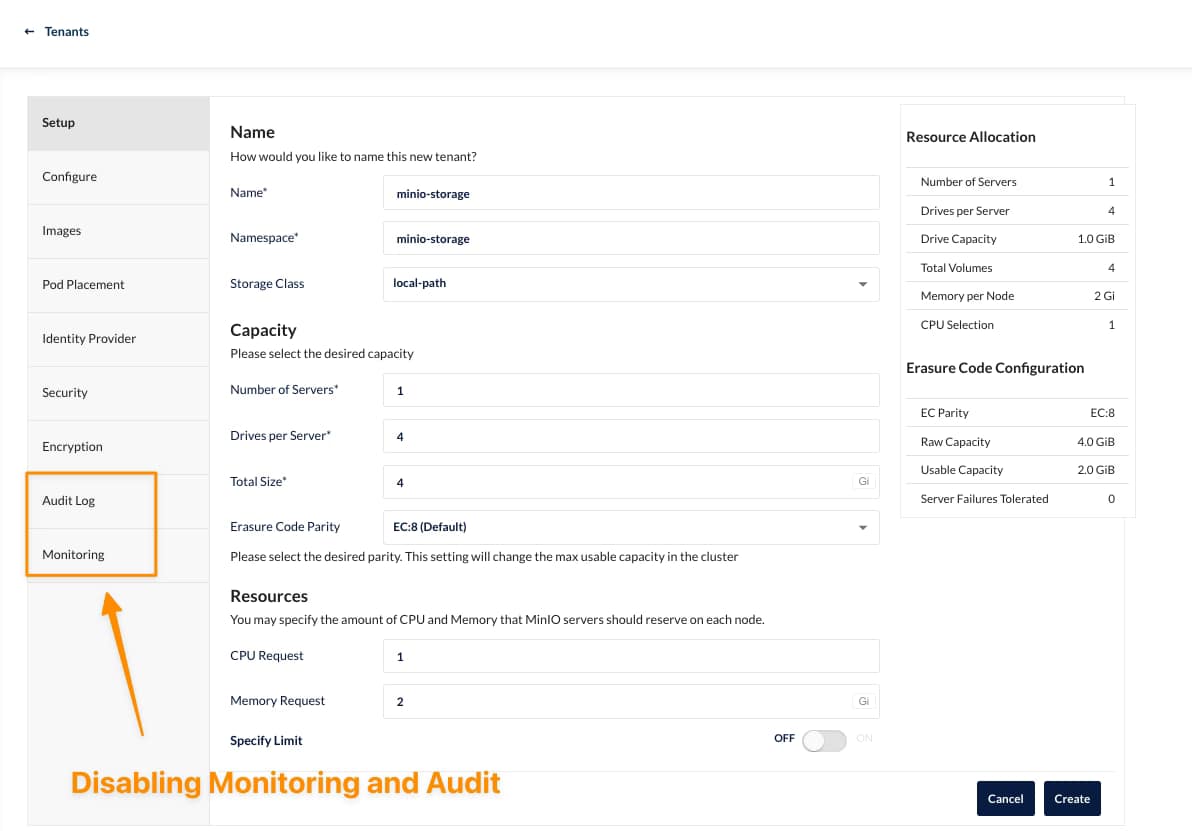

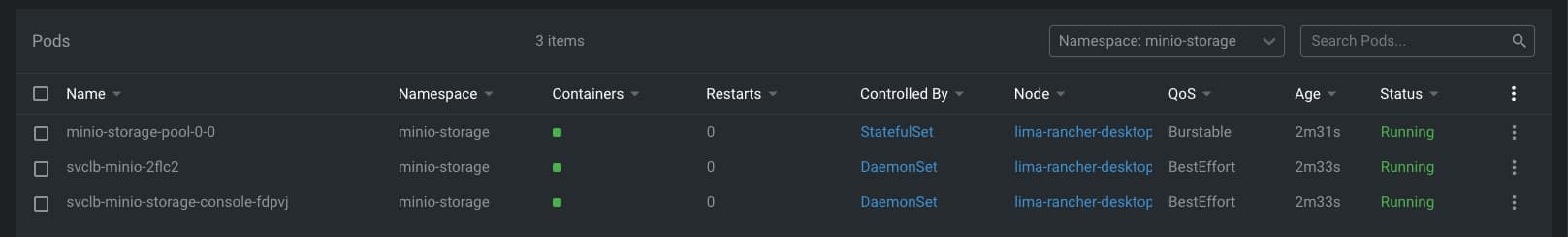

We already covered the deployment models from MinIO. As shown here, you can use its helm chart or the MinIO operator. But, the integration with Loki it’s even better because the helm charts from Loki already included MinIO as a sub-chart so you can deploy MinIO as part of your Loki deployment based on the configuration you will find on the values.yml as shown below:

# -------------------------------------

# Configuration for `minio` child chart

# -------------------------------------

minio:

enabled: false

accessKey: enterprise-logs

secretKey: supersecret

buckets:

- name: chunks

policy: none

purge: false

- name: ruler

policy: none

purge: false

- name: admin

policy: none

purge: false

persistence:

size: 5Gi

resources:

requests:

cpu: 100m

memory: 128Mi

So with a single command, you can have both platforms deployed and configured automatically! I hope this is as useful for you as it was for me when I discovered and did this process.

📚 Want to dive deeper into Kubernetes? This article is part of our comprehensive Kubernetes Architecture Patterns guide, where you’ll find all fundamental and advanced concepts explained step by step.