Kubectl command can be the most used command you can type when working with the Kubernetes ecosystem. As you know, kubectl is the open the door to all the Kubernetes world as pretty much all of our interactions go through that part, unless you are using a CLI approach.

So, based on the productivity principles, if you can improve just 1% in the task that you perform the most, the global improvement will be massive. So, let’s see how we can do that here.

kubectl is a command with many different options that could help boost your productivity a lot. But at the same time, as it has so many options, it is pretty complex to know all of them or be aware that there is a faster way to do the job, and that’s why I would like to add some options here to try to help you with this set of kubectl tips.

Kubectl Commands Tips

Let’s start with the first kubectl commands that help a lot to improve your productivity:

kubectl explain <resource-object>

This command will show the API reference for any Kubernetes Object, so it would help you know the exact spelling of the option that you always miswrite.

kubectl get <resource-object> —watch-output

The —watch-output option added to any kubectl command will work in the same way as the watch command itself, so it will refresh the same command every 2.0 seconds to see the real-time version of that command and avoid that you need to type it again or rely on an external command such as watch

kubectl get events --sort-by=".lastTimestamp"

This command will help you when you want to see the events in your current context, but the main difference is that it will sort the output by the timestamp from more recent to older, so you will avoid needing to scroll to find the latest events.

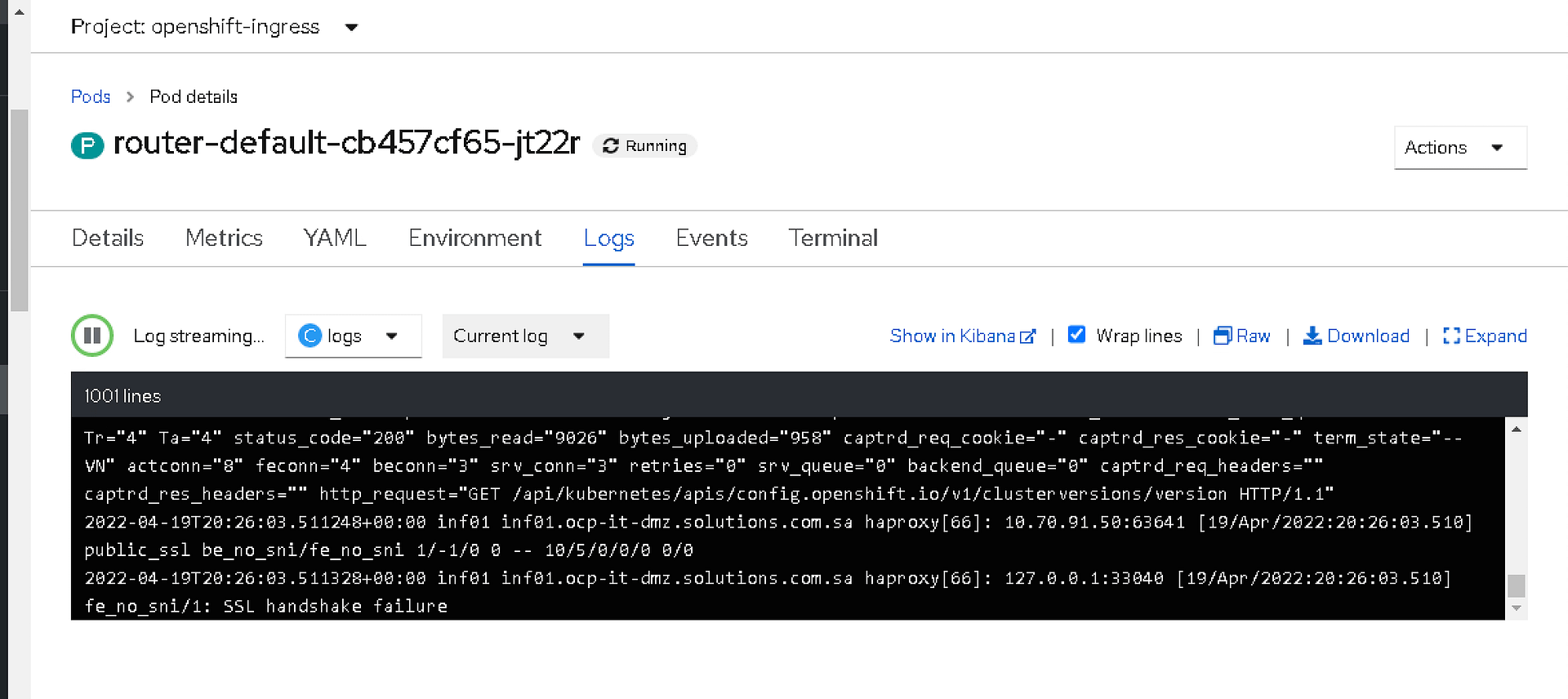

kubectl logs --previous

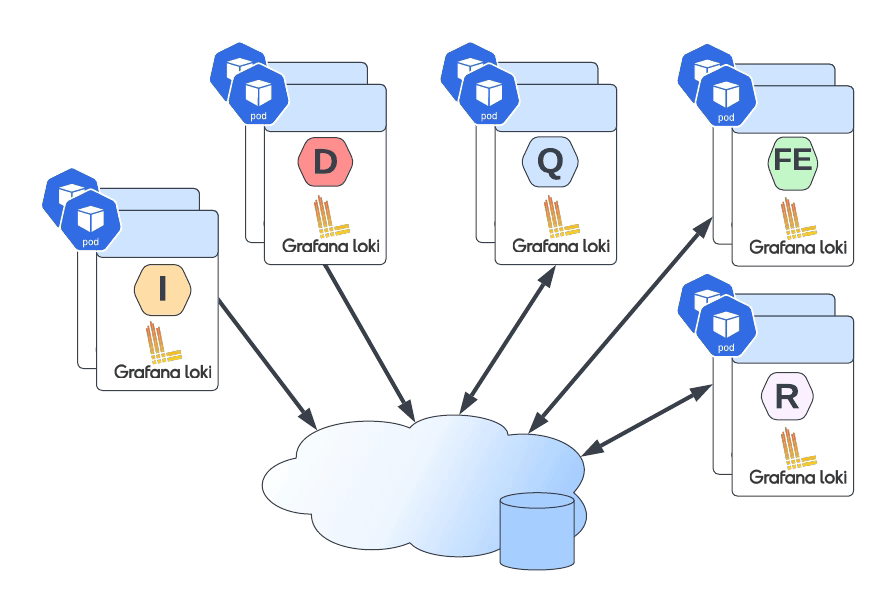

We always talk about one of the needs for a Log Aggregation Architecture because the logs are disposable, but what about if you want to get the logs in a killed container? You can use the --previous flag to access the logs for a recently terminated container. This will not remove the need for a logging aggregation technique, but it will help troubleshoot when Kubernetes start killing things and you need to know what happened.

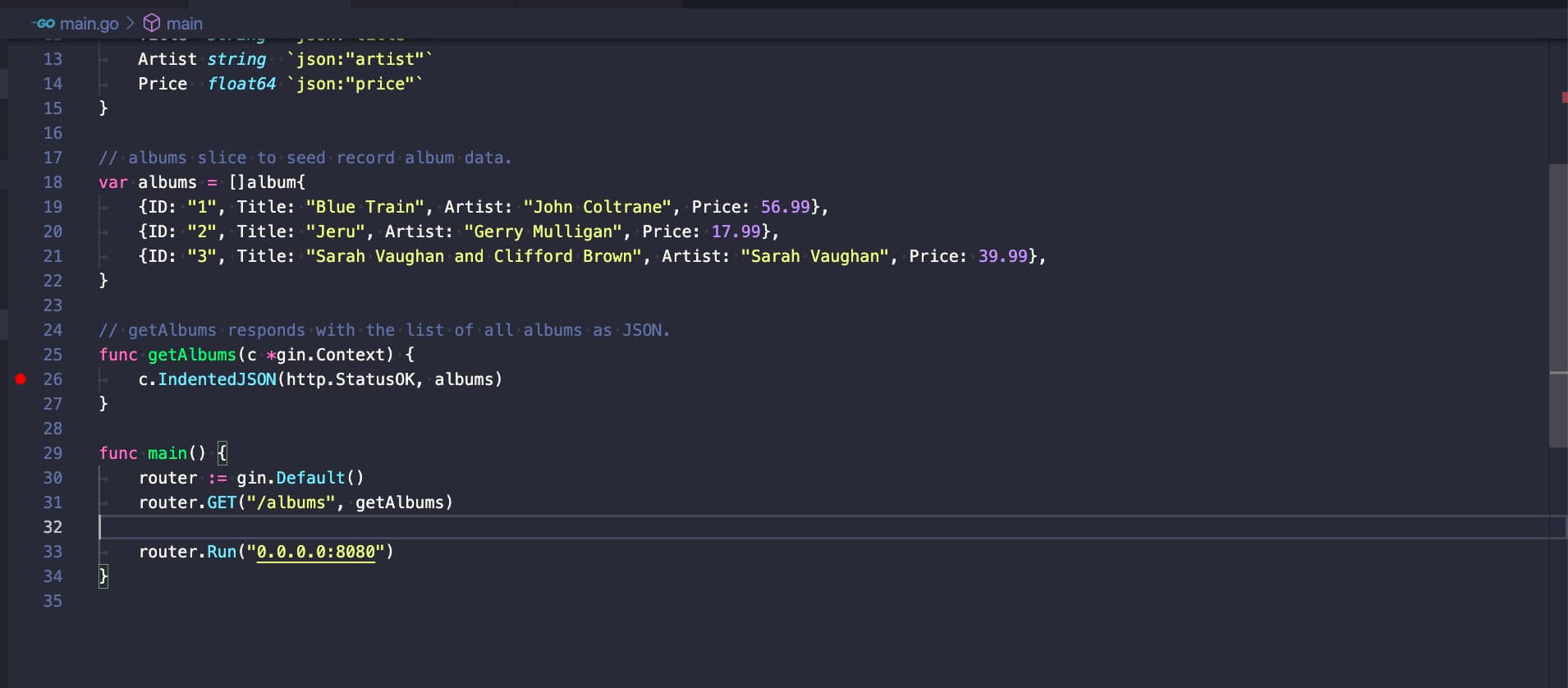

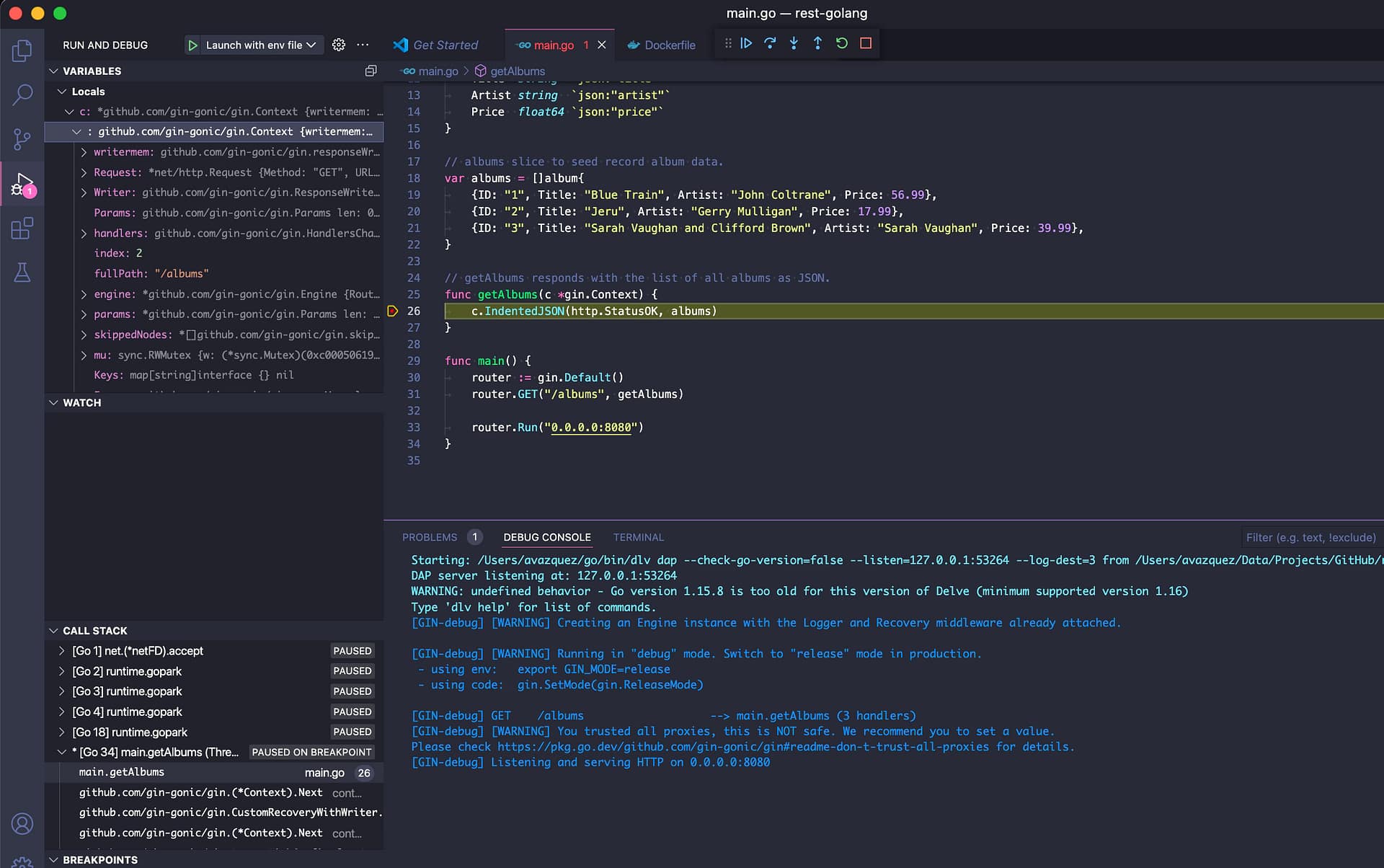

kubectl create <object> <options> -o=yaml --dry-run=client

kubectl create allows us to create an object of our preference by providing the required arguments imperatively, but if we add the -o=yaml --dry-run=client option, we will not get our object created. Instead, we will have a YAML file defining that object. So we can easily modify it to our needs without needing to make it from scratch by searching Google for a sample to start with.

kubectl top pods --all-namespaces --sort-by='memory'

This command will alter the standard top pods order to show the pods and the resources they are consuming, and at the same time, it will sort that output by the memory usage. So, in environments with many pods, it will provide just at the top the ones you should focus on first to optimize the resources for your whole cluster.

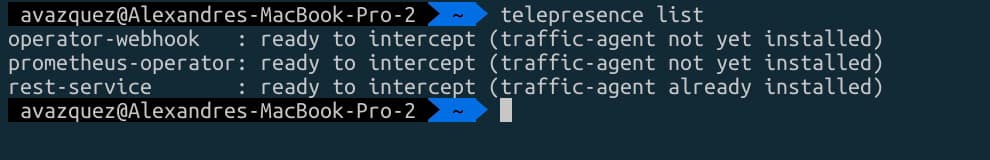

Kubectl Alias

One step beyond that is to simplify those commands by adding an alias to this. As you can see, most of these commands are pretty long as they have many options, so writing each of these options will take a while.

So, if you want to go one step further on this optimization, you can always add an alias to that command to simplify it a lot. And if you want to learn more about those aliases, I strongly recommend the GitHub repo from Ahmet Alp Balkan: