Discover how Init Containers can provide additional capabilities to your workloads in Kubernetes

There are a lot of new challenges that come with the new development pattern in a much more distributed and collaborative way, and how we manage the dependencies is crucial to our success.

Kubernetes and dedicated distributions have become the new standard of deployment for our cloud-native application and provide many features to manage those dependencies. But, of course, the most usual resource you will use to do that is the probes.

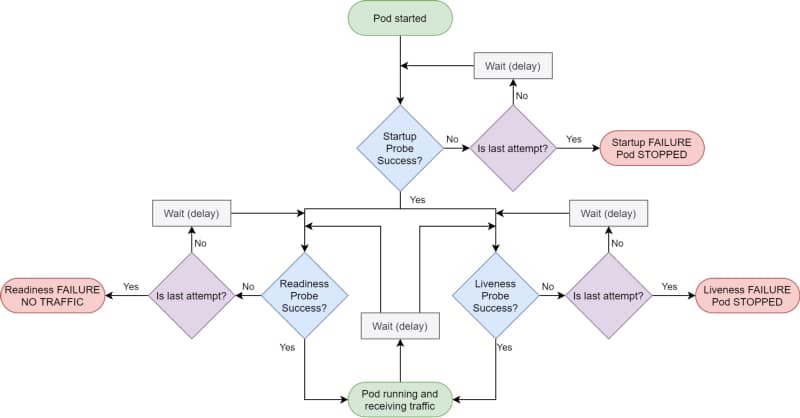

Kubernetes provides different kinds of probes that will let the platform know the status of your app. It will help us to tell if our application is “alive” (liveness probe), has been started (startup probe), and if it is ready to process requests (readiness probe).

Kubernetes Probes are the standard way of doing so, and if you have deployed any workload to a Kubernetes cluster, you probably have used one. But there are some times that this is not enough.

That can be because the probe you would like to do is too complex or because you would like to create some startup order between your components. And in that cases, you rely on another tool: Init Containers.

The Init Containers are another kind of container in that they have their image that can have any tool that you could need to establish the different checks or probes that you would like to perform.

They have the following unique characteristics:

- Init containers always run to completion.

- Each init container must complete successfully before the next one starts.

Why would you use init containers?

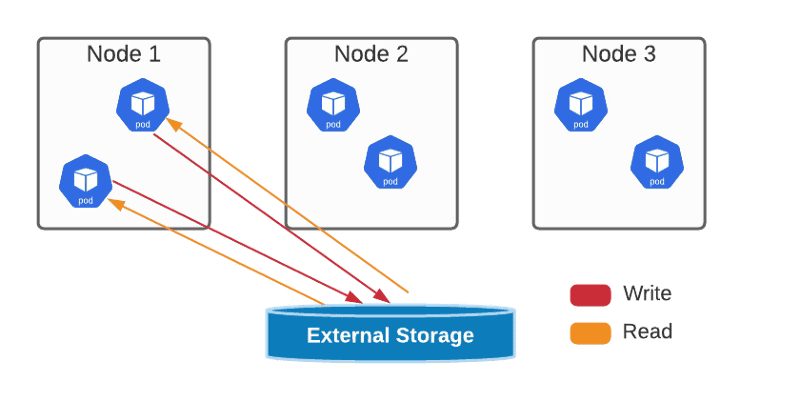

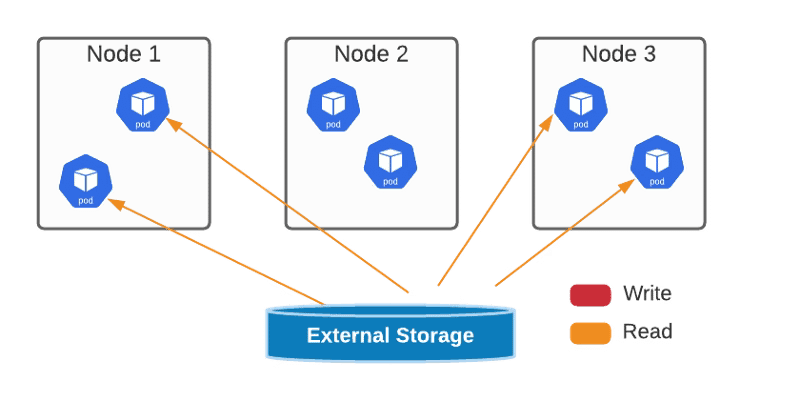

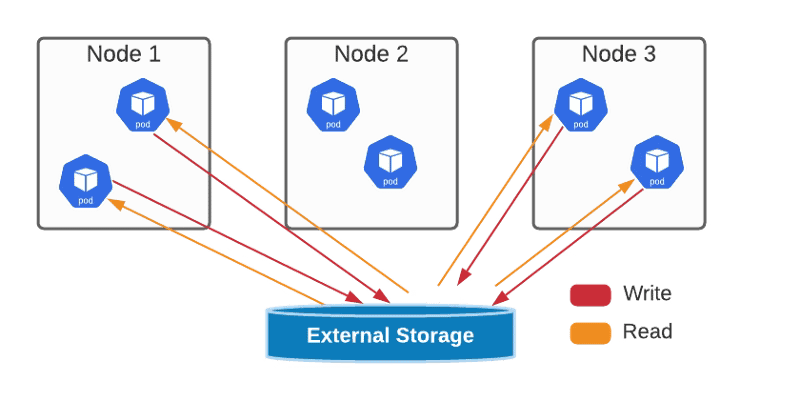

#1 .- Manage Dependencies

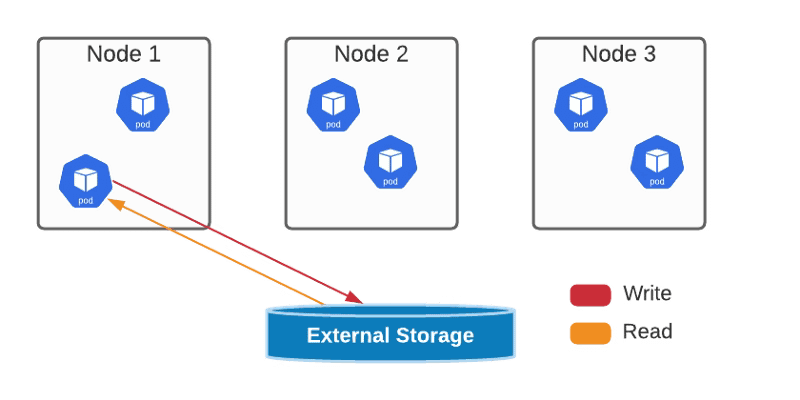

The first use-case to use init containers is to define a relationship of dependencies between two components such as Deployments, and you need for one to the other to start. Imagine the following situation:

We have two components: a Web App and a Database; both are managed as containers in the platform. So if you deploy them in the usual way, both of them will try to start simultaneously, or the Kubernetes scheduler will define the order, so it could be possible the situation of the web app will try to start when the database is not available.

You could think that is not an issue because this is why you have a readiness or a liveness probe in your containers, and you are right: Pod will not be ready until the database is ready, but there are several things to note here:

- Both probes have a limit of attempts; after that, you will enter into a CrashLoopBack scenario, and the pod will not try to start again until you manually restart it.

- Web App pod will consume more resources than needed when you know the app will not start at all. So, in the end, you are wasting resources on the process.

So defining an init container as part of the web app deployment that checks if the database is available, maybe just including a database client to quickly see if the database and all the tables are appropriately populated, will be enough to solve both situations.

#2 .- Optimizing resources

One critical thing when you define your containers is to ensure that they have everything they need to perform their task and that they don’t have anything that is not required for that purpose.

So instead of adding more tools to check the component’s behavior, especially if this is something to manage at specific times, you can offload that to an init container and keep the main container more optimized in terms of size and resources used.

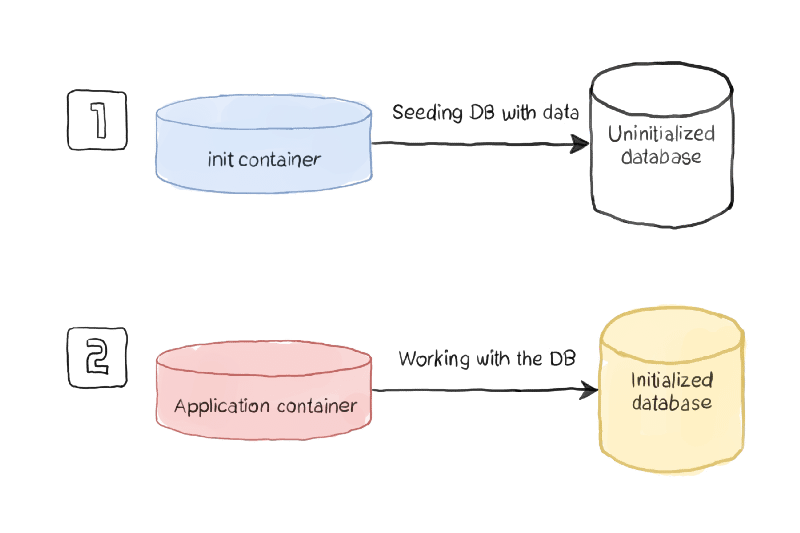

#3.- Preloading data

Sometimes you need to do some activities at the beginning of your application, and you can separate that for the usual work of your application, so you would like to avoid the kind of logic to check if the component has been initialized or not.

Using this pattern, you will have an init container managing all the initialization work and ensuring that all the initialization work has been performed when the main container is executed.

How to define an Init Container?

To be able to define an init container, you need to use a specific section of the specification section of your YAML file, as it is shown in the picture below:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: myapp-pod

labels:

app: myapp

spec:

containers:

- name: myapp-container

image: busybox:1.28

command: ['sh', '-c', 'echo The app is running! && sleep 3600']

initContainers:

- name: init-myservice

image: busybox:1.28

command: ['sh', '-c', "until nslookup myservice.$(cat /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/namespace).svc.cluster.local; do echo waiting for myservice; sleep 2; done"]

- name: init-mydb

image: busybox:1.28

command: ['sh', '-c', "until nslookup mydb.$(cat /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/namespace).svc.cluster.local; do echo waiting for mydb; sleep 2; done"]You can define as many Init Containers as you need. Still, you will note that all the init containers will run in sequence as described in the YAML file, and one init container can only be executed if the previous one has been completed successfully.

Summary

I hope this article will have provided you with a new way to define the management of your dependencies between workloads in Kubernetes and, at the same time, also other great use-cases where the capability of the init container can provide value to your workloads.

📚 Want to dive deeper into Kubernetes? This article is part of our comprehensive Kubernetes Architecture Patterns guide, where you’ll find all fundamental and advanced concepts explained step by step.