All The Power of Object Storage In Your Kubernetes Environment

In this post, I would like to bring to you MinIO, a real cloud object storage solution with all the features you can imagine and even some more. You are probably aware of Object Storage from the AWS S3 service raised some years ago and most of the alternatives in the leading public cloud providers such as Google or Azure.

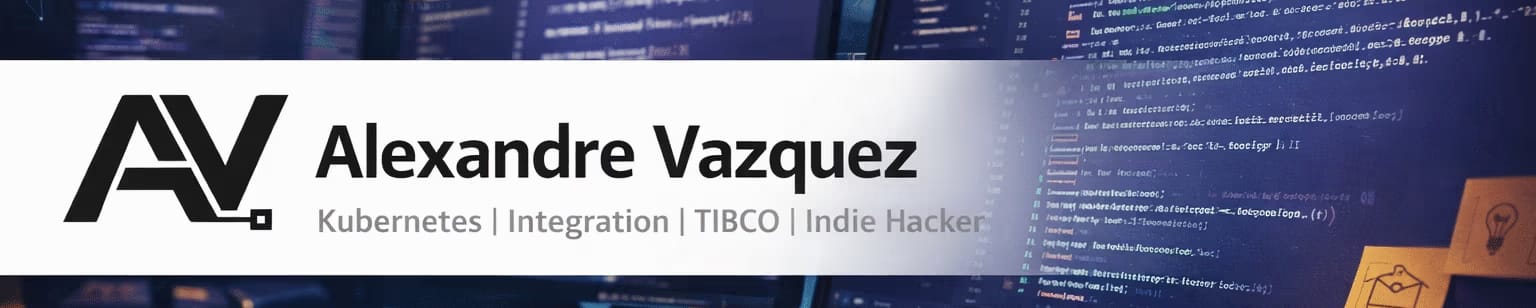

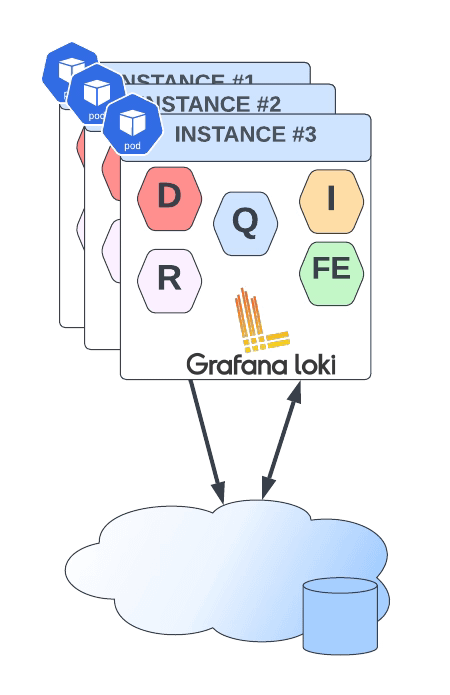

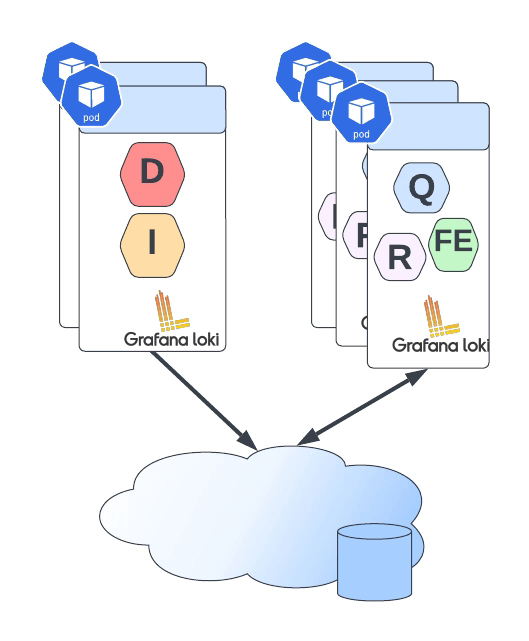

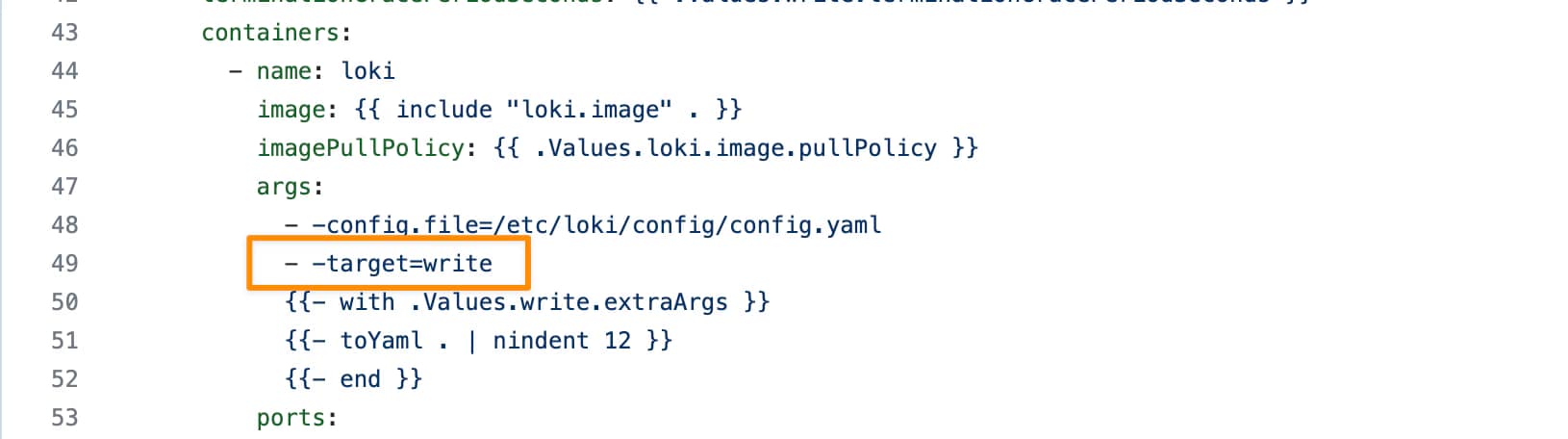

But what about private clouds? Is it something available that can provide all the benefits of object storage, but you don’t need to rely on a single cloud provider. And even more important than that, in the present and future, that all companies are going to be multi cloud do we have at our disposal a tool that provides all these features but doesn’t force us to have a vendor lock-in. Even some software, such as Loki, encourages you to use an object storage solution

The answer is yes! And this is what MinIO is all about, and I just want to use their own words:

“MinIO offers high-performance, S3 compatible object storage. Native to Kubernetes, MinIO is the only object storage suite available on every public cloud, Kubernetes distribution, the private cloud, and the edge. MinIO is software-defined and is 100% open source under GNU AGPL v3.”

So, as I said, everything you can imagine and even more. Let’s focus on some points:

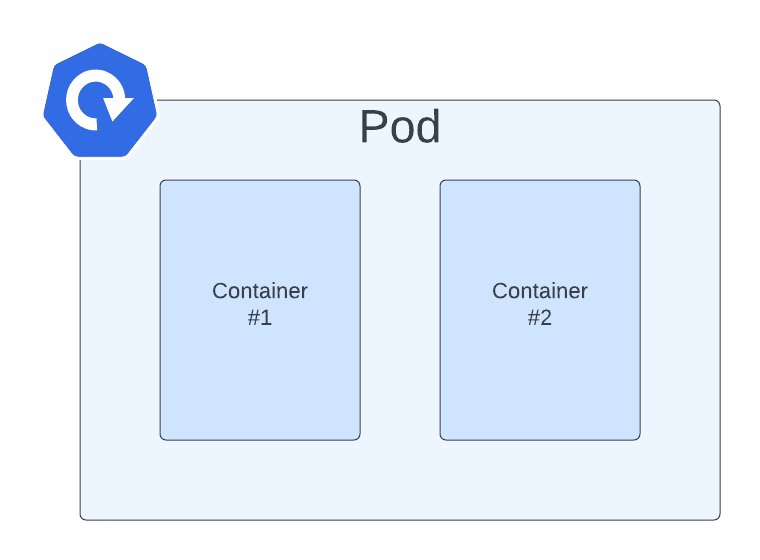

- Native to Kubernetes: You can deploy it in any Kubernetes distribution of choice, whether this is public or private (or even edge).

- 100% open source under GNU AGPL v3, so no vendor lock-in.

- S3 compatible object storage, so it even simplifies the transition for customers with a strong tie with the AWS service.

- High-Performance is the essential feature.

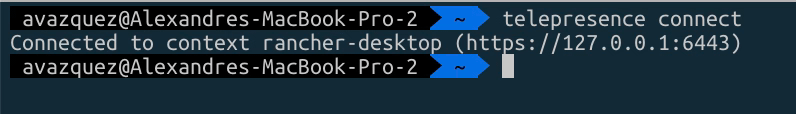

Sounds great. Let’s try it in our environment! So I’m going to install MinIO in my rancher-desktop environment, and doing that, I am going to use the operator that they have available here:

To be able to install, the recommended option is to use krew, the plugin manager we already talked about it in another article. The first thing we need to do is run the following command.

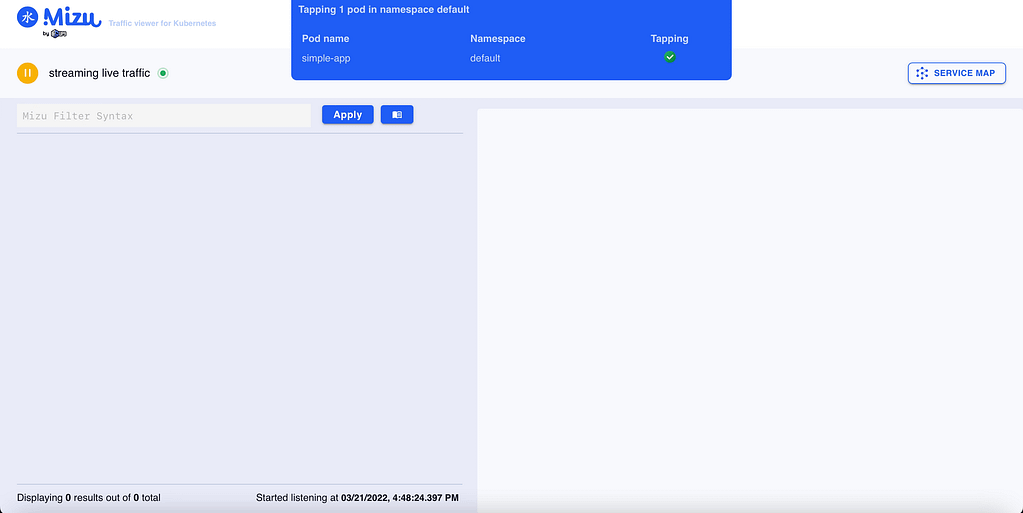

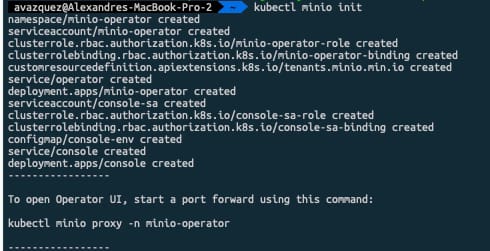

kubectl minio initThis command will deploy the operator on the cluster as you can see in the picture below:

Once done and all the components are running we can launch the Graphical interfaces that will help us create the storage tenant. To do so we need to run the following command:

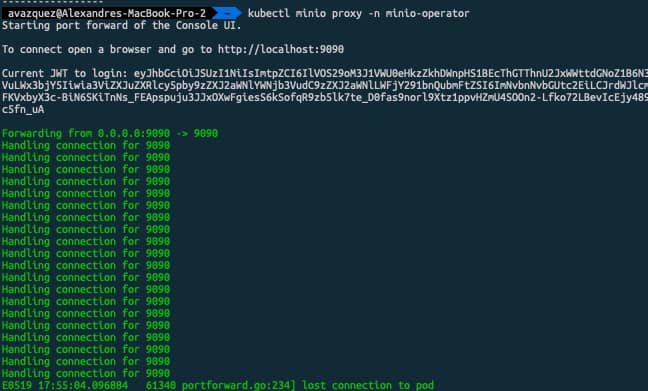

kubectl minio proxy -n minio-operatorThis will expose the internal interface that will help us during that process. We will be provided a JWT token to be able to log into the platform as you can see in the picture below:

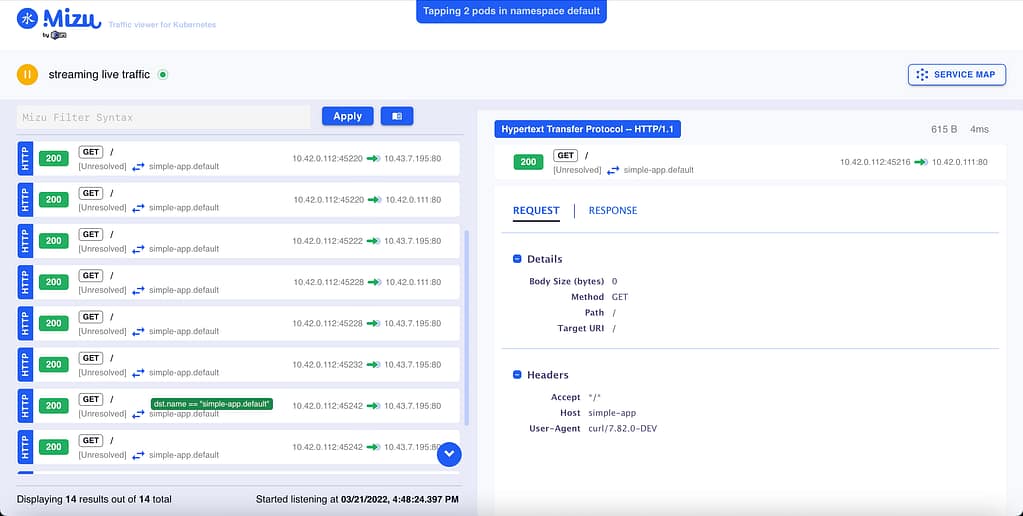

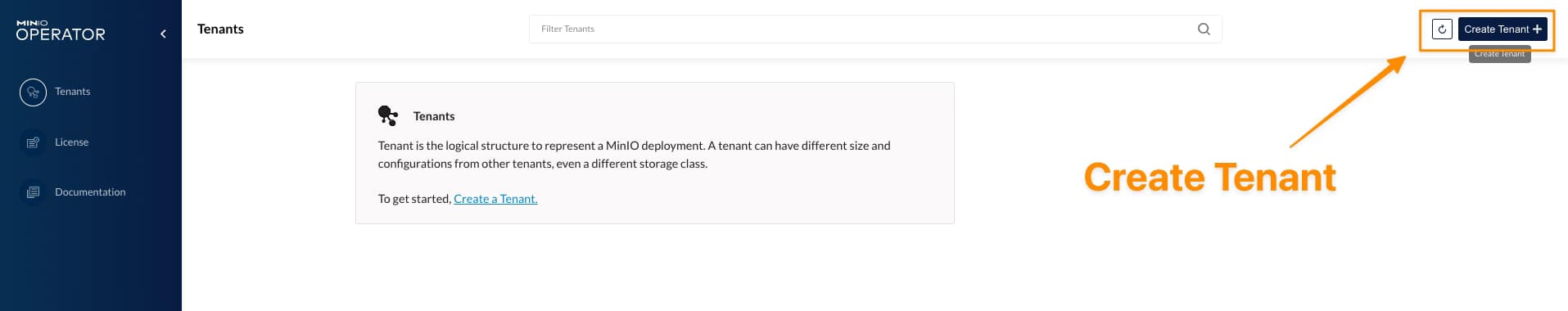

Now we need to click on the button that says “Create Tenant” which will provide us a Wizard menu to create our MinIO object storage tenant:

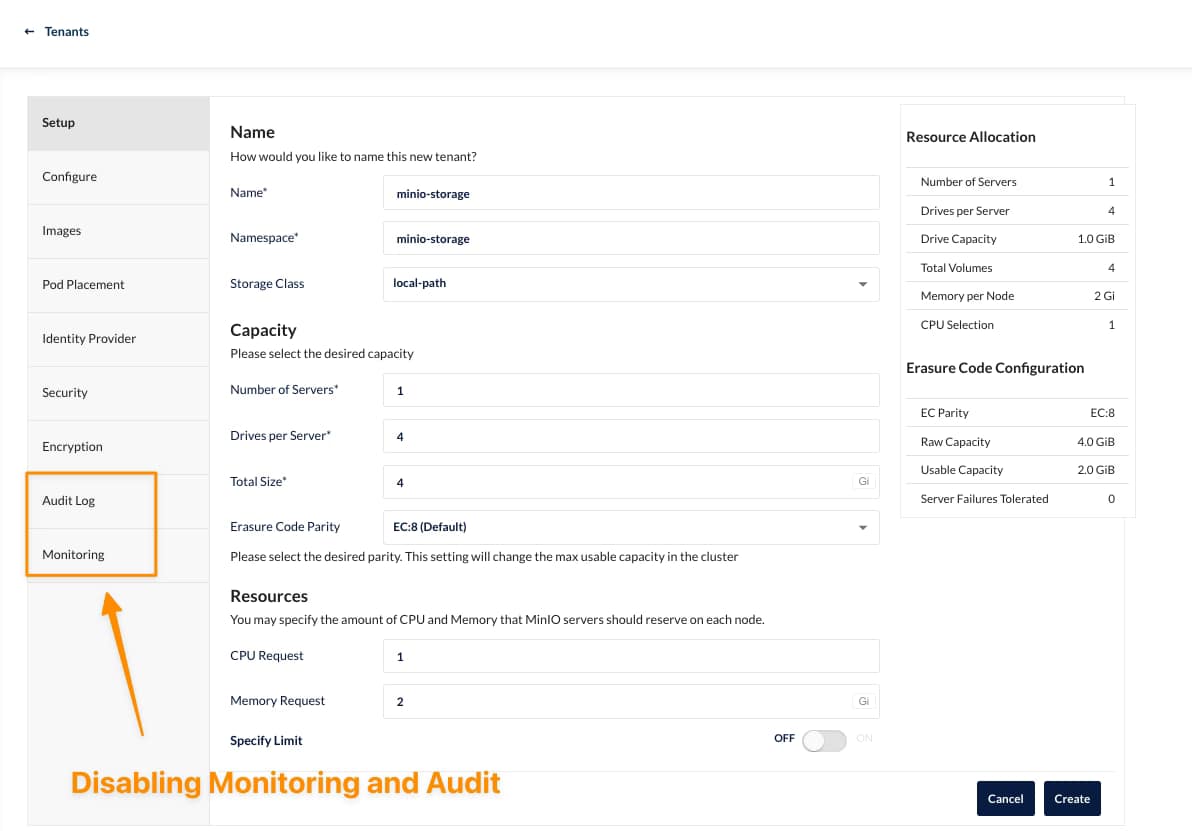

On that wizard we can select several properties depending on our needs, as this is for my rancher desktop, I’ll try to keep the settings at the minimum as you can see here:

It would help if you had the namespace created in advance to be retrieved here. Also, you need to be aware that there can be only one tenant per namespace, so you will need additional namespaces to create other tenants.

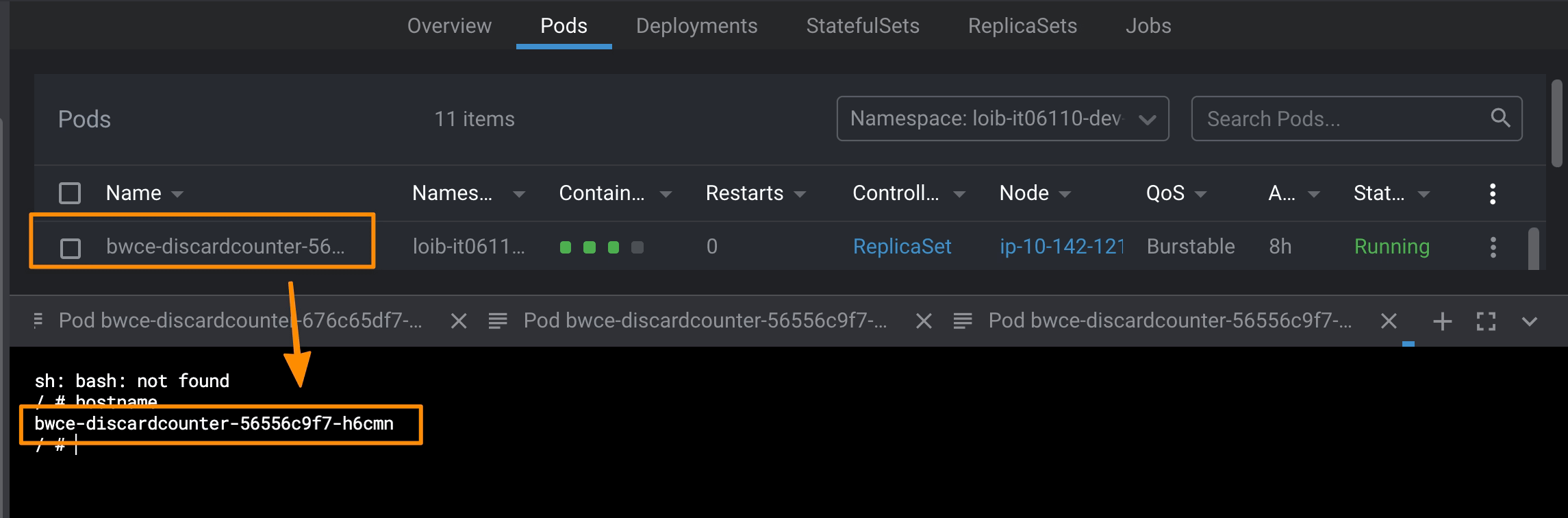

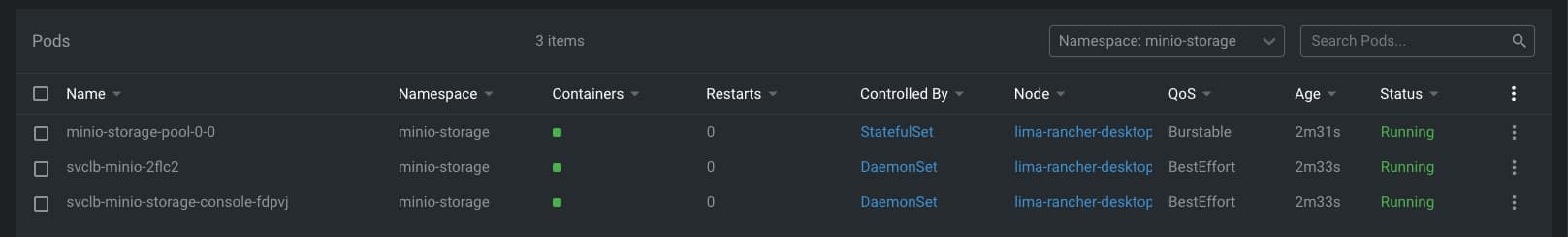

As soon as you hit create, you will be provided with an API Key and Secret that you need to store (or download) to be able to use later, and after that, the tenant will start its deployment. After a few minutes, you will have all your components running, as you can see in the picture below:

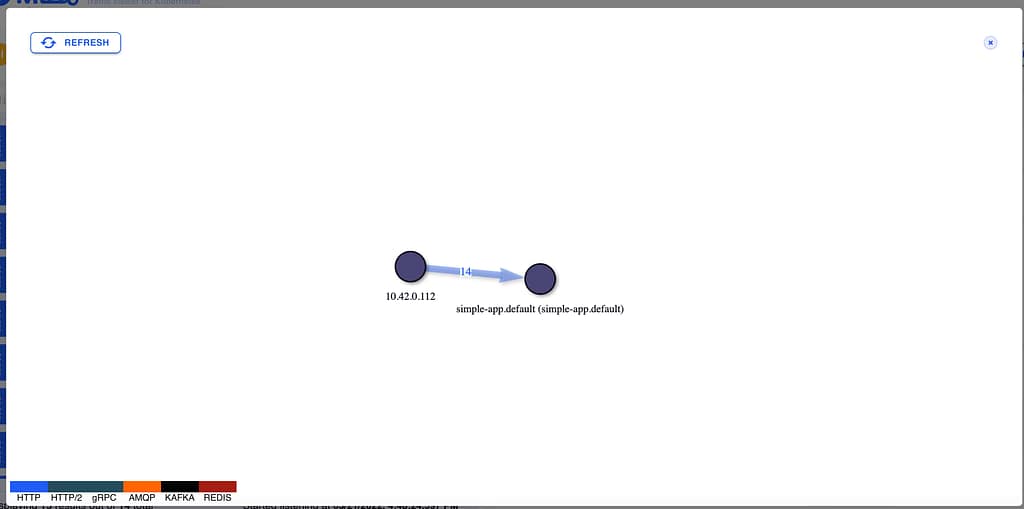

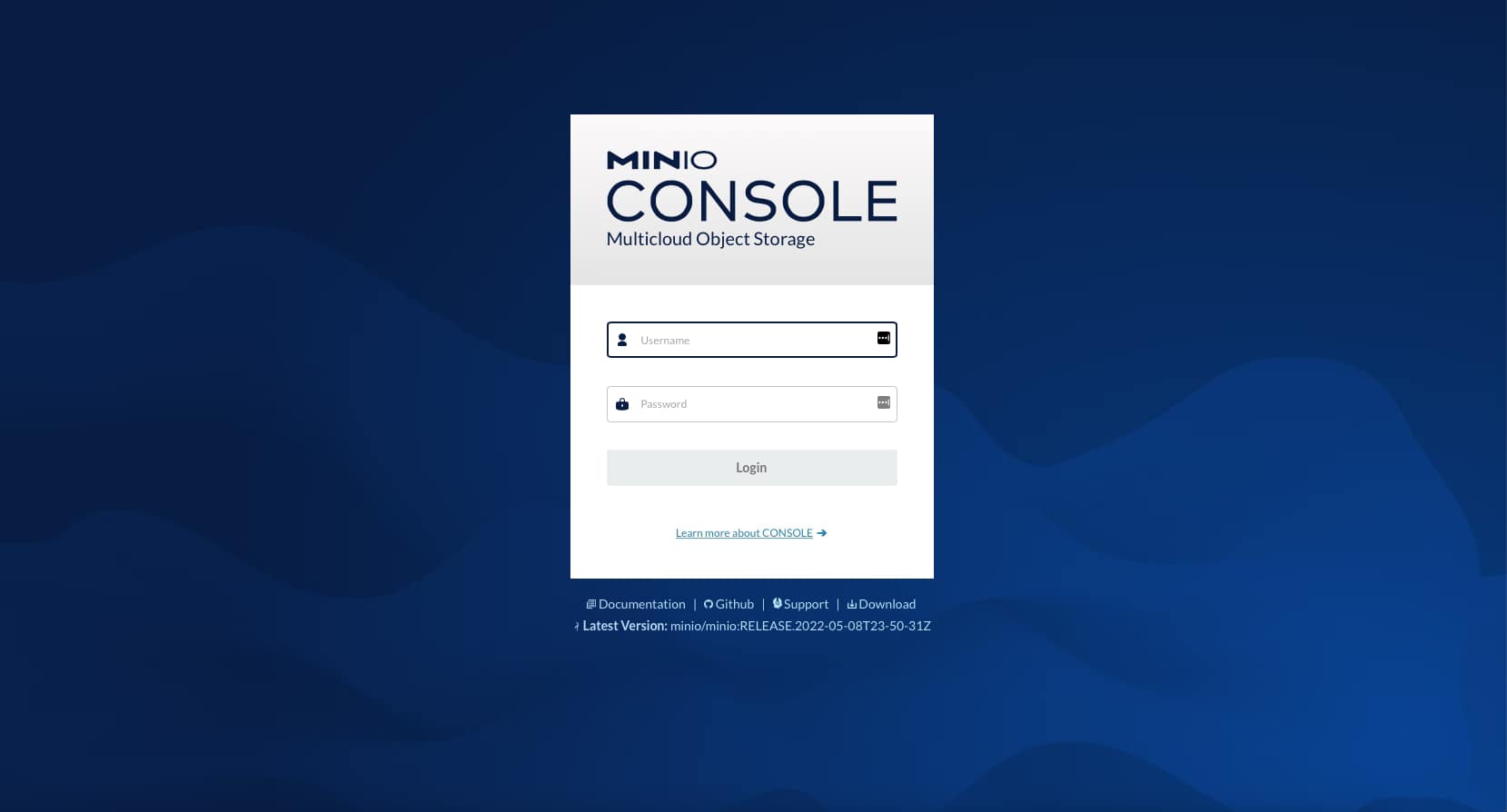

If we go to our console-svc, you will find the following GUI available:

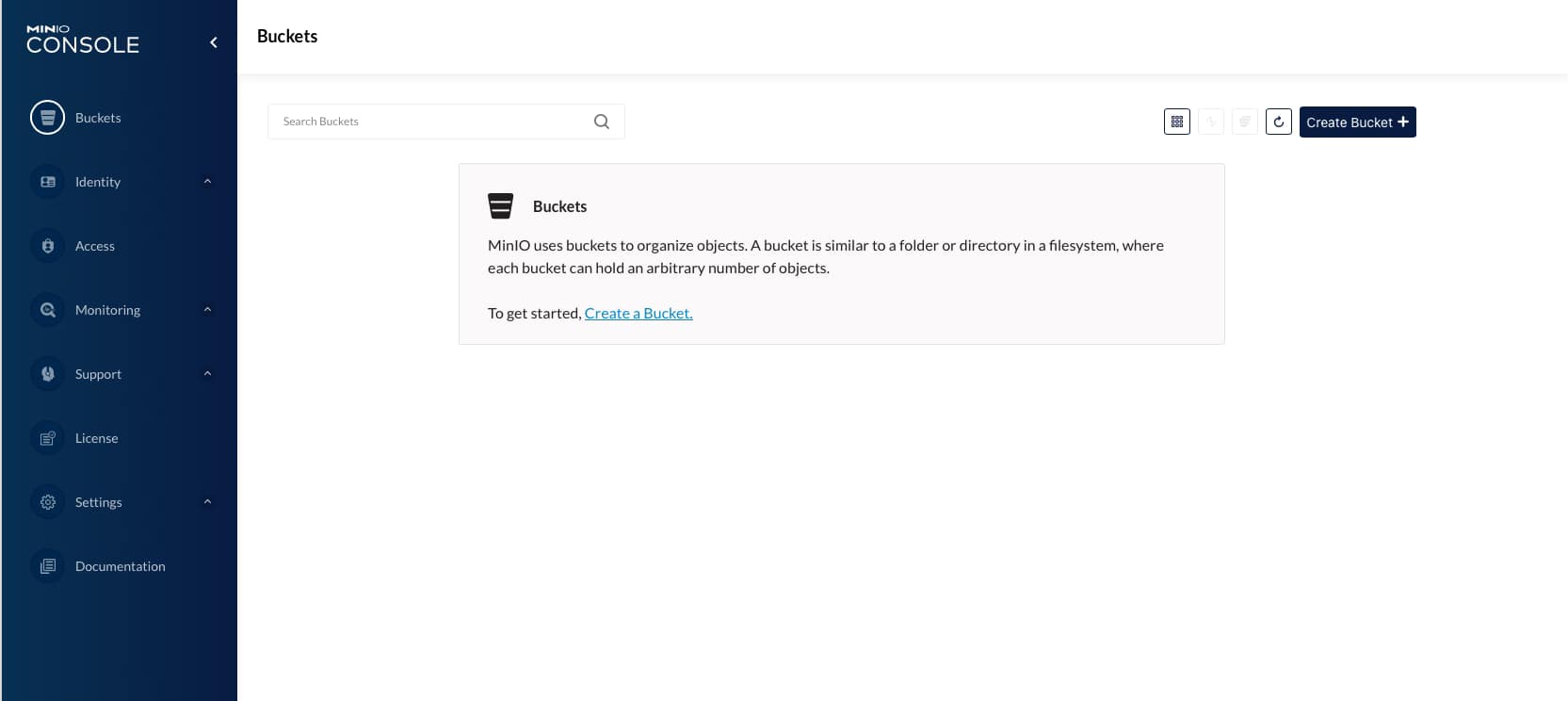

After the credentials are download in the previous step, we will enter the console for our cloud object store and be able to start creating our buckets as you can see in the picture below:

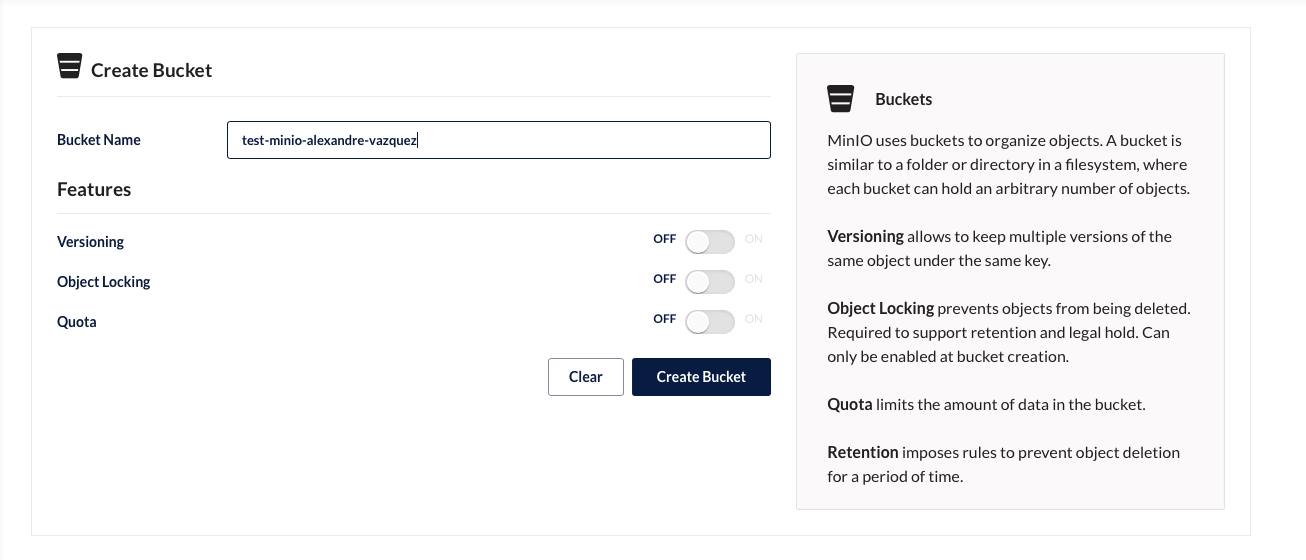

On the screen of creating a bucket, you can see several options, such as Versioning, Quota, and Object Locking, that give a view of the features and capability this solution has

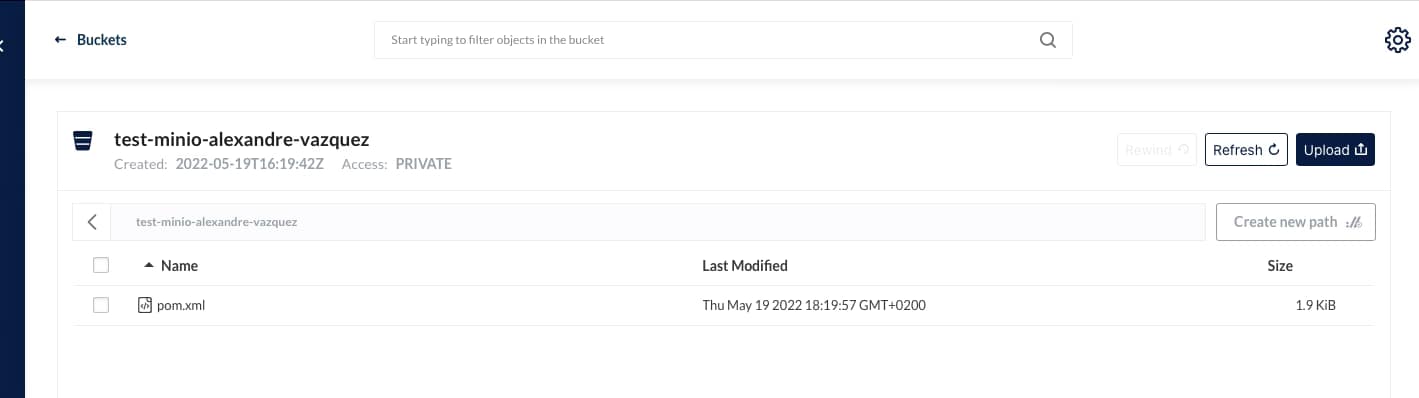

And we can start uploading and downloading objects to this new bucket created:

I hope you can see this as an option for your deployments, especially when you need an Object Storage solution option for private deployments or just as an AWS S3 alternative.

📚 Want to dive deeper into Kubernetes? This article is part of our comprehensive Kubernetes Architecture Patterns guide, where you’ll find all fundamental and advanced concepts explained step by step.