Multi-Stage Dockerfile is the pattern you can use to ensure that your docker image is at an optimized size. We already have covered the importance of keeping the size of your docker image at a minimum level and what tools you could use, such as dive, to understand the size of each of your layers. But today, we are going to follow a different approach and that approach is a multi-stage build for our docker containers.

What is a Multi-Stage Dockerfile Pattern?

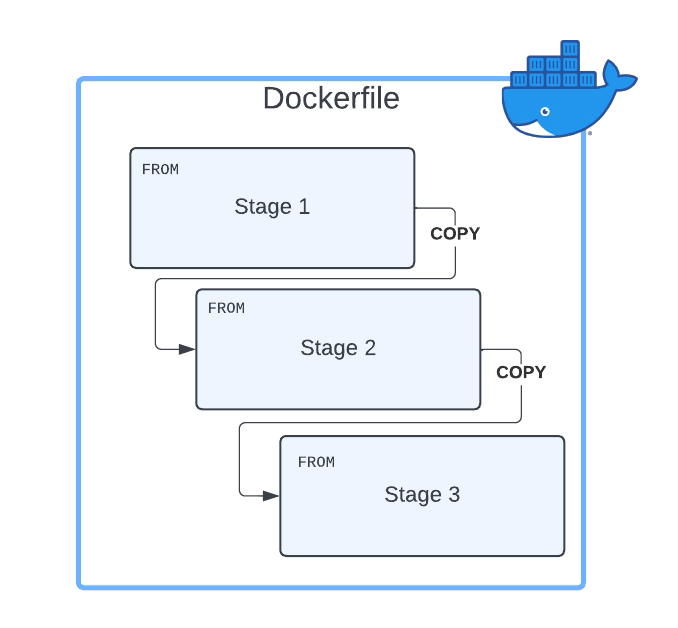

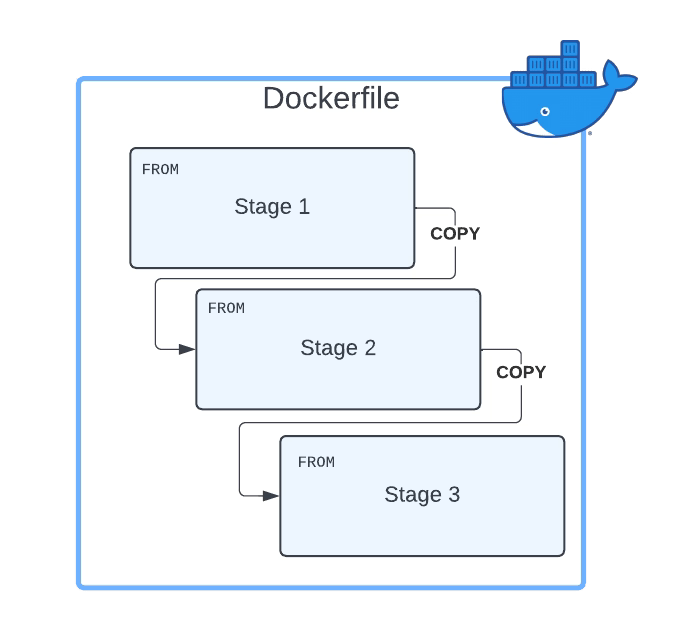

The multi-Stage Dockerfile is based on the principle that the same Dockerfile can have different FROM sentences and each of the FROM sentences starts a new stage of the build.

Why Multi-Stage Build Pattern Helps Reducing The Size of Container Images?

The main reason the usage of multi-stage build patterns helps reduce the size of the containers is that you can copy any artifact or set of artifacts from one stage to the other. And that is the most important reason. Why? Because that means that everything you do not copy is discarded and you are not carrying all these not required components from layer to layer and generating a bigger unneeded size of the final Docker image.

How do you define a Multi-Stage Dockerfile

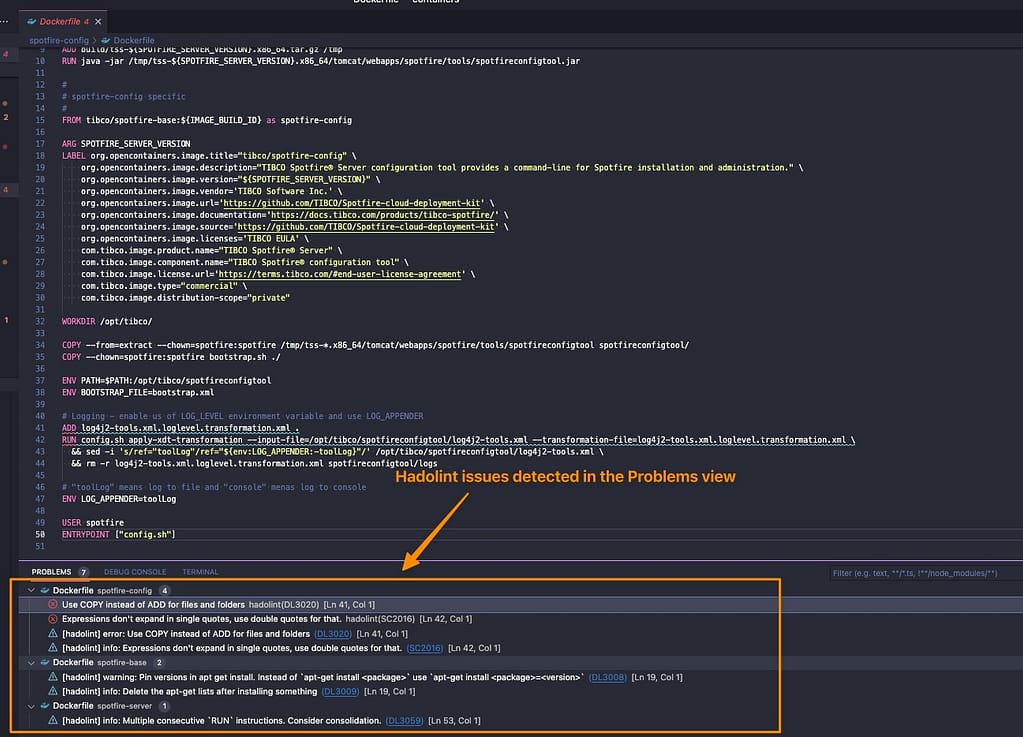

First, you need to have a Dockerfile with more than one FROM. As commented, each of the FROM will indicate the start of one stage of the multi-stage dockerfile. To differentiate them or reference them, you can name each of the stages of the Dockerfile by using the clause AS alongside the FROM command, as shown below:

FROM eclipse-temurin:11-jre-alpine AS builder

As a best practice, you can also add a new label stage with the same name you provided before, but that is not required. So, in a nutshell, a Multi-Stage Dockerfile will be something like this:

FROM eclipse-temurin:11-jre-alpine AS builder

LABEL stage=builder

COPY . /

RUN apk add --no-cache unzip zip && zip -qq -d /resources/bwce-runtime/bwce-runtime-2.7.2.zip "tibco.home/tibcojre64/*"

RUN unzip -qq /resources/bwce-runtime/bwce*.zip -d /tmp && rm -rf /resources/bwce-runtime/bwce*.zip 2> /dev/null

FROM eclipse-temurin:11-jre-alpine

RUN addgroup -S bwcegroup && adduser -S bwce -G bwcegroup

How do you copy resources from one stage to another?

This is the other important part here. Once we have defined all the stages we need, and each is doing its part of the job, we need to move data from one stage to the next. So, how can we do that?

The answer is by using the command COPY. COPY is the same command you use to move data from your local storage to the container image, so you will need a way to differentiate that this time you are not copying it from your local storage but another stage, and here is where we are going to use the argument --from. The value will be the name of the stage we learned in the previous section to declare. So a complete COPYcommand will be something like the snippet shown below:

COPY --from=builder /resources/ /resources/

What is the Improvement you can get?

That is the essential part and will depend on how your Dockerfiles and images are created, but the primary factor you can consider is the number of layers your current image has. The bigger the number of layers, the more significant that you can probably save on the amount of the final container image in a multi-stage dockerfile.

The main reason is that each layer will duplicate part of the data, and I am sure you will not need all of the layer’s data in the next one. And using the approach comments in this article, you will get a way to optimize it.

Where can I read more about this?

If you want to read more, you would need to know that the multi-stage dockerfile is documented as one of the best practices on the Docker official web page, and they have a great article about this by Alex Ellis that you can read here.

📚 Want to dive deeper into Kubernetes? This article is part of our comprehensive Kubernetes Architecture Patterns guide, where you’ll find all fundamental and advanced concepts explained step by step.